It’s been 33 years since Azhar Cachalia was a student at Wits. Back than he had to apply to the government to attend a ‘white’ university, as did all black students – defined as African, Indian and Coloured.

It’s been 33 years since Azhar Cachalia was a student at Wits. Back than he had to apply to the government to attend a ‘white’ university, as did all black students – defined as African, Indian and Coloured.

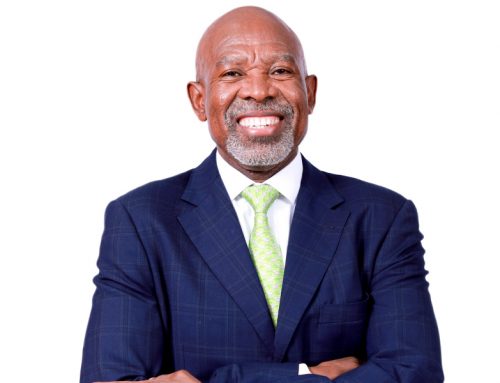

Today he is a Judge at the High Court of Appeal in Bloemfontein, where he has served since 2005.

An activist born and bred, he is as passionate today about the need to create a just, non-racial society with opportunity and growth for all, as he was in his student days.

Talking from his home in Kensington, Joburg, where he flew in from Bloemfontein for the weekend to celebrate his wife’s birthday, he talks about ‘then’ and ‘now’ and how the path of the past and the course of the present are disturbingly converging.

“The thing about activism is that I never give up,” he says. “If I lose hope because of where we find ourselves in our society today then I will lose something valuable in myself, and so I keep on questioning and arguing and fighting to keep society on track. If I stop, I will retreat into abject cynicism and that is not good for anyone.”

His is not an abstract hope. It is a hope based on the very real, humane values of the Freedom Charter and the South African Constitution, for which so many people over so many generations have fought.

“I don’t want to overly romanticize the past, but the extent of non-racialism we built from the 1980s to the mid-90s provided the foundation we envisaged for a new society in South Africa,” he says.

“This is beginning to dissipate and if we are not careful, we will find history repeating itself, as it sadly does tend to do. New leaders often mimic old leaders and old systems. It takes hard work to transform. There is more than enough evidence to show that things can go horribly wrong, and if your transformation is only skin deep, you simply dress up the same old problems in a different colour.”

To explore the depth of Cachalia’s words we head back 33 years to find a 23-year-old student on Wits campus studying African Government as part of his BA, towards his BA LLB.

“There were literally a handful of black students on campus back then, all with ministerial approval, but the numbers were starting to grow,” he recalls. “Some had come from the ethnic or bush colleges and had lost a year or two through the ’76 upheaval.”

Cachalia explains how he never felt any discomfort about race despite being on a predominantly white campus where his younger brother Feroz, also a well-known activist, soon joined him.

“We are from a politicized family and we were brought up to believe there was nothing inferior or superior about us,” says Cachalia whose family has been active in the ANC and the Indian Congresses going back to the 1950s. They were part of the defiance campaign and suffered banning and exile.

In their time, Azhar and Feroz were detained and banned several times in the course of their student activism and after they graduated. The reasons for the arrests ranged from distributing pamphlets in commemoration of June 16 to detention under the State of Emergency regulations.

As students they founded the Benoni Student Movement (their family lived in Benoni) and Azhar became Vice-President of the Black Students Society at Wits in 1981.

The Benoni Student Movement targeted disadvantaged students and learners from the surrounding community, with the aim of helping them to apply for bursaries to university, as well as helping the then Standard 9 and matric pupils to overcome any learning problems they might have so that they could achieve university entrance passes.

The Black Students Society (BSS) was formed at Wits in the mid-70s. “It emerged from the black consciousness movement but under our leadership it took a strong, non-racial character that was more ANC aligned,” Cachalia explains.

“We welcomed alliances with white students on a common anti-apartheid programme and worked closely with white student leaders in NUSAS and the SRC.”

By that time the earlier black student movement, the South African Students Organisation (SASO), founded in 1969 had been banned (in 1977). SASO did not believe that black and white students could find common ground.

“SASO’s standpoint was that whites were part of the problem and therefore could not be part of the solution,” Cachalia explains.

“This tension has persisted through to today where even in the governing party there are strands of ethnic or racial chauvinism, which is essentially the reverse of white nationalism.”

This goes against the founding principles of non-racialism in the ANC and fuels the apartheid divide of ‘Us’ and ‘Them’, continues Cachalia who graduated with his LLB in 1983.

The founding of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in the 1980s provided a brief window of the South Africa that people like Cachalia had envisaged. He was an executive member of the UDF until 1990.

“To build up the UDF we used the best skills of all races and in a short period we were able to overcome the legacy of many years of apartheid and racial divide,” he continues.

“The strength of the organisation was that we shared a common goal: to end apartheid and to build a non-racial, truly democratic society. We established a genuine connection between races, communities and students. The white students, instead of feeling alienated, felt very much part of it.

“Yet, instead of building on this togetherness, today white South Africans are constantly reminded of their whiteness, that their role is to repent for the sins of the past, and that they have no intrinsic value as citizens and human beings. This explains why many White South African wonder whether they have a future in this country.

“In the apartheid era it was the same. Those who had skills in the black community were excluded from building the society, and many black South Africans were compelled to leave the country, either to continue the struggle for democracy or to seek better opportunities,” continues Cachalia who says the end result, apart from the damage done to South African society is that we are struggling to compete with other developing countries that use all the available skills at their disposal.

Regarding policies like affirmative action, Cachalia says, “I do not believe that policies like affirmative action were ever meant to guarantee access to position regardless of one’s skill.”

Affirmative action, he explains, was meant to give all marginalised people access to skills and to develop their potential through proper training programmes.

“Unfortunately this is not happening in many institutions and part of the reason for the service delivery demonstrations around the country is because people have been put into jobs they haven’t got the skills to execute.

“Seventeen years into our democracy we should surely have got to a stage where affirmative action should be deracialised to give all marginalised or disadvantaged South Africans who have difficulty accessing education and skills programmes the opportunity to develop and contribute to society.

“The current approach puts race at the centre of affirmative action policy and I believe this is one of the main sources of racial polarization. White South Africans feel alienated and Black South Africans believe that they are entitled to be appointed to positions whether or not they are able to do the job.”

Cachalia says the way that Affirmative Action and BEE is playing itself out currently, only a small section of the community benefits.

“The truth is that we haven’t changed much through BEE. We have simply shifted resources to a small group of black people who happen to be politically connected. BEE thus far has failed and it has been at the expense of job creation and at the expense of building a successful, prosperous, non-racial society.

“The time has come for our programmes to be aimed at tackling all forms of current structural disadvantage and discrimination on a non-racial basis rather than on the basis of historically imposed racial categories,” says Cachalia who believes that all South Africans must continue doing everything in our power to keep striving for the South Africa of which we dream.

If ever there was a man who lives his activism, here he is. A man who attributes much of who he is today to his time at Wits.

“My university experience was very important to me formatively,” he says. “Not just the academic and professional skills I gained, but the resilience to navigate a complex society – which I think is more important than learning to be a good doctor or a good lawyer.”