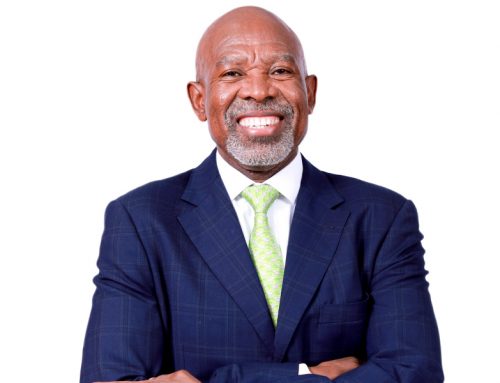

He loves Mathematics, sudoku and jogging. He believes that understanding our place in the universe is far more important than the accumulation of material possessions. Meet the new Vice-Chancellor of Rhodes University, Dr Sizwe Mabizela.

If you’re on the streets of Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape at 4.30 in the morning, you might see the Vice-Chancellor jogging past.

“It’s a wonderful time of the day and it is one of the aspects of Grahamstown that makes living here so enjoyable. I can jog and enjoy the beauty of creation and the fresh air,” says Dr Mabizela.

Jogging energises him for the very long day ahead. On most nights his office light burns deep into the night.

“Long hours don’t bother me, I enjoy my work,” he says. “I find the university environment very stimulating and I cannot imagine myself anywhere else but in an institution of higher learning.”

Dr Mabizela is a professor of Mathematics and has been at Rhodes for 10 years. He was the absolute frontrunner for the position of Vice-Chancellor, out of 17 applications.

He has served as the Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Academic & Student Affairs at Rhodes from 2008 to the present. Prior this, he was the Head of the Department of Mathematics (Pure and Applied) from 2004 to 2008.

He has also been the acting Vice-Chancellor of Rhodes University since the departure of the former Vice-Chancellor, Dr Saleem Badat, in July this year. After eight years at Rhodes, Dr Badat resigned to take up a post in New York with the Andrew W Mellon Foundation Higher Education Programme.

In South Africa, where mathematics is emphasised as a key study area for future graduates, Rhodes now has a mathematical maestro at its helm.

“I love mathematics, and have done so since childhood,” says Dr Mabizela, who has a PhD in Parametric Approximation from Pennsylvania State University in the United States.

“The beauty of mathematics is that it inculcates in one ways of thinking systematically and innovatively about the widest range of challenges.”

The mathematics approach to problem solving, he explains, is to first break down the problem into “manageable chunks” rather than trying to deal with the problem in its entirety.

From here you tackle each of the chunks, using the power of logic and argument.

“At each stage of the process you rigorously interrogate your assumptions, and from here you will hopefully have found a way forward towards solving the bigger problem,” he says.

The biggest problem we currently face in South Africa, he believes, is that, “we live in a globalised world in which there is a hegemonic dominance of the neoliberal free market logic, which makes the market the main thing. This breeds a society where people are preoccupied with the accumulation of personal wealth above all else,” he explains.

As the new Vice-Chancellor he aims to lead by example in producing graduates who are not consumed with material gain.

“I have never had dreams of vast financial wealth, owning a multi-storey home or driving a fancy car. What is important is to gain knowledge that can help us understand our natural environment, human interactions and our place in the universe,” he explains.

“It is all about developing a deeper understanding and appreciation of how we can live in this world in a sustainable manner, and in a manner that fosters social cohesion.

“And if, along this path, our graduates acquire significant material wealth, then my hope is that they will use it to make a change in the lives of those who are less fortunate in material and educational terms.”

Dr Mabizela grew up in Ladysmith, KwaZulu Natal and matriculated in 1980 from St Chad’s High School in Ladysmith.

His mother, Sibongile Mabizela, was a nurse and his late father, Christopher Mabizela, was a teacher.

“They were very loving parents who instilled in us the importance and value of education,” he explains. My father constantly reminded us that he didn’t have any material possessions to bequeath us but what he could do for us was to make sure we received quality education.

“My mother was a wonderful role model and she had a big influence on my interest in mathematics as she was very good at it. I was fascinated by it, and it came naturally to me. I was also very fortunate to have excellent mathematics teachers all the way from primary school through secondary school who developed my love of mathematics and gave me challenging problems, over and above the standard homework, to keep me interested.”

This led to him enrolling for a BSc at the University of Fort Hare in 1981.

At that time, as a black person, you needed a ministerial permit to study at the so-called ‘white’ universities, and you could only get one if the so-called ‘black’ universities did not offer the particular degree programme you wanted to pursue. The BSc was not one of these.

“Those were highly turbulent political times,” Dr Mabizela recalls.

“The government of the day had granted nominal independence to Ciskei, which included Fort Hare, and as students we were involved in the resistance movement against apartheid and its homeland policies.”

The University of Fort Hare had such a rich history of educating struggle stalwarts that they were not going to allow it to be associated with the homeland government.

“We fought pitch battles with the police, the university was closed down on several occasions, and, along with several of my peers I was arrested in 1983 because of my role in student protests and in the mobilisation of the United Democratic Front (UDF) against the government,” Dr Mabizela continues.

“The people we looked up to were Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki, all of whom were on Robben Island. To find out what was happening in the liberation struggle, we would huddle around the radio and listen to Radio Freedom, which was broadcast on short wave from Lusaka, Zambia,” recalls Dr Mabizela who completed his Honours and Masters in Mathematics at Fort Hare, and was awarded a scholarship in 1986 to do his PhD in the United States.

“It was a wonderful era in certain ways because the level of political consciousness was very high and most of us were united in the common cause of liberating the country from apartheid.

“People like Archbishop Desmond Tutu also had the foresight to set up scholarships for black South Africans to study in the United States, with the aim of preparing us to play a role in a free and liberated South Africa.”

Thirty years later, however, he says: “As a nation we have lost our way, we have lost our moral compass; which is a great tragedy. Unbelievable levels of corruption, consumerism and materialism have engulfed the ideals that we held so dear, and the vision we had for this country.

“We could never have imagined that so many of those who were at the forefront of the liberation struggle would be the first ones to be so seduced by material possessions. It is a terrible disappointment.”

What does he feel can be done to re-find our way as a nation?

“We need a revolution,” he laughs. “But this is a different kind of revolution – it is the kind that can help us to realise our own humanity; something that can only reach its fullness if we affirm, defend and advance the humanity of others.

“This requires a revolutionary way of being,” he explains. “Not one where we carry arms – but instead one guided by our wonderful constitution, and based on the principles of human rights, human dignity, social justice, non-sexism and equality; one that truly subscribes to that time honoured African philosophy of Ubuntu.”

The role of universities in creating such a society, he adds, is to produce graduates who are thoughtful, critical and engaged citizens: “These are citizens who would want to be agents of social change and societal transformation, who would use their education and positions of power and influence to advance the cause of those who are less fortunate.”

The role of schools is equally important to develop citizens with a caring heart and a deep value of education, says Dr Mabizela who serves on the schools’ Maths Olympiad Committee and helps to set the problems – something he loves doing.

He and his wife Dr Phethiwe Matutu who is the Chief Director of the Department of Science and Technology, share a love of mathematics and education, which they impart to their 12-and14-year-old daughters, Zinzi and Zama.

“They are both at Victoria Girls in Grahamstown, which is a top class government school that represents what all government schools in South Africa should be like,” he says.

“We deliberately chose a government school because we wanted our girls to interact with others from diverse social, cultural and economic backgrounds so that they do not become elitest in their way of being and can grow as well-rounded young girls ready to find their place in our society.”

The girls are boarders at Victoria Girls as Dr Matutu is based in Pretoria and commutes between here and Grahamstown as often as she can. She joined the Department of Science and Technology after a long career as an academic, at three universities: the Universities of Cape Town and Stellenbosch, and Rhodes. She has a PhD in pure Mathematics from the University of Cape Town.

She and Dr Mabizela met when he was an academic at the University of Cape Town and she was working on her PhD. “We fell in love with each other and realised how much we wanted to be together, it’s that simple,” he says.

For him it is not a problem that his wife works in Pretoria:

“My wife is inspired by her position at the Department of Science and Technology, and that is important to me. We make the distance issue work for us and have done so for six years,” says Dr Mabizela who is available to the girls when they need him, as his office is two minutes from Victoria Girls.

“It’s another big advantage of being in Grahamstown. As an academic with a family here, you have a choice of excellent public and private schools, and you are close by if your children need you.”

From his new office, Dr Mabizela will seamlessly assume his new role. For some time he has been leading the development of an Institutional Development Plan (IDP) for Rhodes – it’s a strategic document that will be the institution’s compass for the next 10 years.

“In the process of formulating the IDP we have identified seven Grand Challenges,” Dr Mabizela explains.

The seven challenges are to:

- Ensure financial sustainability of the Univeristy;

- Improve staff remuneration and salary competitiveness;

- Improve staff and student equity profile and advance transformation;

- Modernise systems, processes and procedures;

- Attend to infrastructure maintenance;

- Find funding for financially in need students; and

- Engage the local municiplaity to ensure provision of basic services such as water, sanitation and electricity.

He has applied himself to develop innovative ways to address each of these challenges.

To address academic equity, for example, he aims to ensure, inter alia, the continuation of the Next Generation Academic Programme at Rhodes, which focuses on attracting and developing top-achieving black and women academics to Rhodes.

Recent studies have shown that almost 20% of academics will retire in the next ten years, including half of the professoriate.

Since its inception in 2001, 41 new lecturers have participated in the 3-year Next Generation Academic Programme at Rhodes, which is the model being used to develop a national programme for all universities in South Africa.

“Our approach should be premised on- and guided by the principle of pursuing ‘equity with quality and quality with equity’, which our former Vice-Chancellor, Dr Badat, so eloquently advocated,” says Dr Mabizela who has been hailed as “the first black African Vice-Chancellor of the 110-year-old institution that is Rhodes”.

“I don’t want us to be hung up on this,” he says. “For me it is whether the university has identified a suitable and competent person to serve as its Vice-Chancellor and provide leadership for the institution at this time.

I am deeply honoured and humbled to have been invited to serve as the Vice-Chancellor and I use the word serve advisedly, as my model of leadership is about serving, and something I hope to clearly demonstrate over the next seven years.”