So we have a population explosion and a food crisis, and we have to find alternatives to meet the protein needs of large volumes of people on our planet. Enter fish farming or aquaculture, which is definitely the way of the future, says Gavin Johnston, who holds a Master’s degree in ichthyology from Rhodes University and is a founding partner of Aqua Pemba, an offshore dusky kob farm in Mozambique.

So we have a population explosion and a food crisis, and we have to find alternatives to meet the protein needs of large volumes of people on our planet. Enter fish farming or aquaculture, which is definitely the way of the future, says Gavin Johnston, who holds a Master’s degree in ichthyology from Rhodes University and is a founding partner of Aqua Pemba, an offshore dusky kob farm in Mozambique.

“Everyone’s accustomed to cattle, chickens, sheep and goats being farmed, and the newest entrant to our market is fish farming or aquaculture. This is in line with the global trend where a vast percentage of the fish and seafood eaten worldwide today is farm-raised,” he explains.

In our part of the world the trend’s on the rise, with fish farmers now operating from Paternoster on the West Coast to East London, to KwaZulu-Natal, to Pemba in Mozambique on the east coast.

It takes the pressure off wild populations, such as the delicious dusky kob, also known in SA as daga salmon, kabeljou or boerkabeljou. A very similar fish from the same family is known as meagre in Europe, red drum in the USA and mulloway in Australia.

In South Africa the dusky kob – traditionally one of the most important inshore commercial and recreational linefish species – is still caught as a non-targeted species or bycatch by inshore trawl fisheries. The fish is in deep trouble with spawning stocks down to an estimated 1-4.5% of their original numbers. Accordingly, South African commercial line-caught or trawl-caught dusky kob is currently on the Southern African Sustainable Seafood Initiative’s (SASSI) Red List. Red-listed fish populations have either collapsed and/or of extreme environmental concern and/or lack adequate management, or are illegal to buy or sell in this country.

Fish farming appears to be the perfect solution for the survival of this and other species, and consumers often believe they’re “buying green” when they choose farmed fish. But this isn’t always the case: the production of farmed fish needs to be carefully scrutinised. Are we being fooled into paying top dollar for farmed fish that isn’t as green as we think it is?

If we look at one form of farming dusky kob in South Africa, where it is produced on land in tanks, we see that it is Green-listed by SASSI. Green-listed species can handle current fishing pressure, or are farmed in a manner that does not harm the environment. But how do we know the dusky kob we are buying is definitely responsibly farmed when it can look exactly the same as its bycatch counterpart, which is Red-listed by SASSI?

“We are concerned about this and it certainly does cause confusion in the marketplace when a product isn’t properly labelled and there isn’t adequate traceability. Which is why we emphasise the importance of this to fish farmers and all fish and seafood producers as part of best practice,” says Chris Kastern, the Seafood Market Transformation Manager for WWF-SA’s Marine Programme, which includes SASSI.

SASSI encourages wholesalers, retailers, restaurants and consumers to examine what they’re buying and ask where and how it was caught or farmed.

“They’re extremely important questions because, in addition to the bycatch issue, fish that come from a farm are only as good as they’re looked after,” says Johnston. “If they’re fed well in good, clean water, and not stressed from too much human interaction or kept in too confined a space, they definitely look and taste better.”

Farmed dusky kob varies in size from 500grams-4kilograms. “The size of farmed kob may often be smaller than that of the legal minimum size for wild-capture kob in your region. If you are in any doubt, ask your seafood vendor for further information about the fish they are offering for sale and insist on adequate labeling,” advises Kastern.

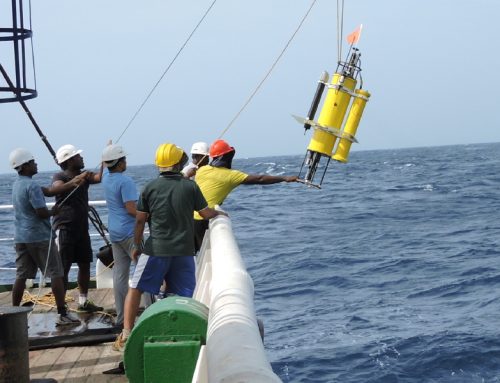

Farmed fish are farmed either on land in tanks housed in buildings into which seawater’s pumped, or in open-air ponds into which seawater’s pumped, or offshore.

“Offshore farming is the way most farmed fish in the world are produced; it’s the most economical approach and it comes with both benefits and risks,” says Johnston. “You can have escapees or a chance of disease breakouts but if you manage the fish well, they reward you with good health, good growth and great taste.”

The effluent factor from all fish farms is a concern. With offshore fish farming, the waste products – including faecal material, uneaten food and the carbon dioxide and ammonia that fish produce – return directly to the ocean. Onshore farms are supposed to treat effluent in environmentally friendly ways before this happens.

The diet of farmed fish is another issue, as it usually consists of pellets of fishmeal from wild pelagic species, such as sardines, pilchards and anchovies.

“One kilogram of fishmeal should give you one or more kilograms of farmed fish to be sustainable, but the reality of the world market is that people want predatory fish – like salmon and dusky kob – more than they want pilchards or anchovies, so the sustainability ratio doesn’t always hold,” Johnston explains.

Aqua Pemba sources its fish feed from a company in Mauritius that uses fish offal, soya and binders combined with wild-caught pilchards and anchovies. There’s a considerable input cost, as they need to feed the fish from hatchlings to adults, which takes 24-30 months.

“To make money, you need to produce 1500-2500 tons a year and we’re currently on 250 tons per year in our second year of production,” says Johnston. “We need to significantly upscale, but Mozambique works in dollars, which certainly aren’t favouring us right now.”

They chose Pemba in Mozambique because of its excellent fish farming potential with deep, protected bays and stable temperatures.

The ultimate green goal for all fish farmers would be to achieve a level consistent with the international Aquaculture Stewardship Council’s (ASC) environmental standards for aquaculture producers. SASSI recognises the ASC as a credible eco-label for farmed seafood species.

The ASC currently has standards for 12 species globally, including abalone, freshwater trout, tilapia and salmon. Farms aiming to be ASC-accredited are independently audited against the council’s standard of best practice for a particular species. The farm’s supply chain component is also audited for traceability best practice, so that when a consumer picks up a product bearing the ASC logo, they know it’s responsibly farmed and can be traced all the way through to the farm.

Hopefully, the ASC will one day have a broad standard that would include farm-raised dusky kob, which could then carry this logo. Meanwhile, we need to keep asking questions and sifting through the many shades of green.

SA’S EXCEPTIONAL MARINE DIVERSITY

SA has approximately 2 000 fish species and 10 000 species of marine invertebrates and plants.

KNOW YOUR GREEN, ORANGE AND RED SPECIES

A nifty Know Your Seafood pocket guide can be downloaded from SASSI’s website for instant referencing to the Green, Orange or Red status of your favourite fish and seafood. Alternatively, SMS the name of the fish/seafood to 079 499 8795 and you’ll receive immediate confirmation of its status.

http:// www.wwf.org.za/sassi