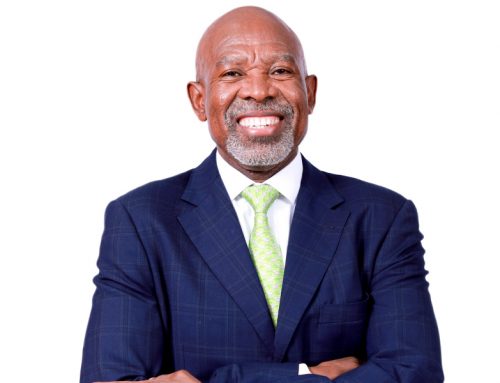

“Going to Scotland to do my Masters in Law was one of the best choices I ever made in my life,” says Professor Nqosa Mahao who is originally from Lesotho and who has a Masters in Law from the University of Edinburgh and a PhD from the University of the Western Cape.

“Going to Scotland to do my Masters in Law was one of the best choices I ever made in my life,” says Professor Nqosa Mahao who is originally from Lesotho and who has a Masters in Law from the University of Edinburgh and a PhD from the University of the Western Cape.

“That Scottish experience turned a young boy who grew up in a village in a small country in Africa into someone with a global outlook who is self-reliant and who is far more broad-minded on a whole range issues. I suffered from a bit of a culture shock at first because it was such a different environment to what I knew, with people from so many different cultures and subcultures,” he explains.

Coming from a conservative African society, his eyes were opened, amongst other things, to women behaving in a far more liberated fashion. “Where I come from you wouldn’t find a woman walking alone at night to a pub as a matter of course, whereas in Scotland women feel free to do this and to talk to whoever is there.”

Another culture shock for the young Mahao was to experience gay and lesbian meetings being openly held, with everyone welcome to attend. “You’re taken aback at first, but then you process it and you realise it’s simply a different side of life.”

He learnt yet another side of life from one of his supervisors in the law Faculty, Zenon Bankowski, a self-proclaimed anarchist. “I was always on the radical side of politics but I never imagined that anyone would proudly proclaim himself to be an anarchist, particularly in law, because it goes against the very notion of conventional law. But there was Zenon Bankowski, an extremely intelligent guy in the Law Department, having written highly insightful books on the subject. The whole experience was so uplifting,” says Mahao.

The great irony was that, unbeknown to him, Bankowski was known to Lesotho’s late King Moshoeshoe II who studied law, philosophy and political science. What would a king and an anarchist have in common? Mahao discovered on his return.

“When I completed my Masters I was invited to the royal palace in Lesotho to present a paper and I had occasion to speak to King Moshoeshoe II. “Zenon had told me that a gentleman once visited him who had mentioned he was the King of Lesotho. I wanted to know if this was true and King Moshoeshoe II confirmed it. He told me he had read Zenon’s books and that he had traveled to Scotland to meet him out of curiosity.”

Mahao describes King Moshoeshoe II as “intellectually adventurous, a social democrat and a difficult, learned man on the left of the political spectrum, which is an unusual place for a king.” His reign ended in 1996 when he was killed in a road accident. He was succeeded by his son, King Letsie III, who is currently reigning and who did his undergraduate degree at the University of Lesotho at the same time as Mahao.

Mahao also met his South African wife Pumela Xundu there. “Thousands of students came from South Africa to study at the University of Lesotho in those days. It was a small but cosmopolitan university, and several well-known South Africans studied there, including Tito Mboweni and Njabulo Ndebele.”

Mahao became head of the Department of Public Law at the University of Lesotho in 1996, Dean of the Faculty from 1999 to 2001 and Pro Vice Chancellor in 2000. He was subsequently appointed Executive Dean of the Faculty of Law at the Mafikeng campus of the North West University. His UNISA post followed.

Between 2004 and 2005 he did a postgraduate diploma in Conciliation and Arbitration through a cohort of universities, including the Universities of Cape Town, Lesotho, Zimbabwe and Namibia.

“The programme was funded by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the Swiss government. Its aim was to introduce mechanisms similar to South Africa’s CCMA dispute resolution system (introduced in 1994) to the rest of the Southern Africa, including Botswana and Swaziland,” explains Mahao who helped set up the cohort when he was Dean of Law at the University of Lesotho, in collaboration with the Deans of Law at the Universities of Cape Town and Namibia.

A proponent of equity in the courts, he explains that these dispute resolution mechanisms do not give precedence to technicalities, as frequently happens in the conventional courts. “They’re aimed at getting directly to the heart of issues and expediting resolutions to avoid long and costly court cases. They are also accessible to the ordinary worker as they don’t pay for the service.”

A proponent of just and fair systems in general, Mahao is well suited to Wits, which, as he says “prides itself on being a liberal institution”. At the same time he recognises this brings with it certain difficulties when driving vision “because everyone has to buy into your vision, which can make it far more difficult and time-consuming to manage”.

Part of Mahao’s vision as the new Dean is to help address the crisis in the whole of higher education in South Africa and the rest of Africa. He terms it “the crisis of relevance of education and that of the aging cohort of knowledge producers”.

“As Dean I will be emphasising the culture of research throughout the five schools in my faculty and strengthening our competitive research edge. In this office I am not an academic, I am a businessperson and I need to look at the bottom line, which is constituted, among others, by research output. The more PhDs, postgraduate programmes and publications we have, the better it is for our international rankings and the overall quality of education at Wits.”

It concerns Mahao that much of the research being produced is by older academics, from 50 to retirement age: “It strikes me that there was a hiatus period when South African universities were not sufficiently nurturing academics to become good researchers. Hence the old guard is producing much of the research, and, as they start exiting the system we need to ensure the baton is passed to the younger generation. It’s a tiger we must tame and we must ride the challenge.”

Mahao also believes the current retirement age at Wits of 65 may need to be reviewed and extended. “We cannot afford to lose the intellectual production and memory of our older academics,” says Mahao who recommended that the retirement age at the University of Lesotho be extended to age 70 while he was Pro Vice-Chancellor there. It was accepted.

Adding to this challenge, the faculty has had a high turnover of deans and heads of schools in the past ten years, which has affected continuity. “We need to get out of this mode and develop a stable leadership that can take a hard look at what needs to be changed.”

At 55 he has demonstrated his dedication to his profession, and fulfilled his late father’s wish that he should make a career in law.

“It’s curious how these things turn out,” says Mahao whose son Mahao Mahao (18) is currently studying law at Rhodes University. “I didn’t want to put any pressure on him to study law, but that is what he has chosen whereas when I was his age I didn’t have a choice. From the age of seven my father told me I would be a lawyer because I would always deliberately play the contrarian. He was convinced that I was far too argumentative to work for any employer.”

By the time Mahao got to university his father had passed away and he told his mother that he intended to study medicine. “At that point she led me to a large metal trunk in our home and told me to open it,” he recalls. “In the trunk were a pile of law books that my father had bought for me through the years, which my mother had safely stored until I was ready to go to university. ‘Do you think these books will help you study medicine?’ she asked. I shook my head and she said ‘Then you know what you need to do’.”

The story has great pathos because by the time Mahao enrolled for law the books were outdated “but I read them anyway and some were very fascinating”, says Mahao who, with hindsight, is pleased he did law.

“I’ve had a wonderful career because of law and there have been so many serendipitous links. For example, in one of the books on interesting legal stories that my father bought for me, it describes a case where a certain medical doctor, a Dr Smith, had improper relations with his patient and was struck off the role.

“It fascinated me at the time but I didn’t think about it for years, until it came up again while I was working on a project with a team from the University of Lesotho and the University of Edinburgh. Through the project I met the famous writer Alexander McCall Smith who is also a professor of medical law, and who invited me to his house for dinner in Edinburgh one evening. During the course of the conversation he told the story of his grandfather, a certain medical doctor, a Dr Smith…”