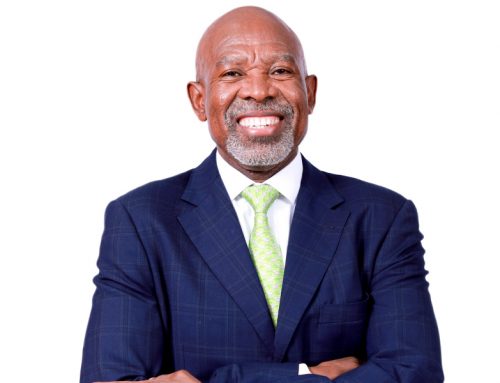

“You can’t biologise or racialise culture. My idea of knowing myself in the world is African, but my skin colour is not the determinant. This reduction of people to one template of colour is vicious racism and something that was weaponised by history. But it is not culture. Culture is a complex of multi-layered realties of knowing oneself and how one lives one’s life.” These are the words of Dr Sam Nzioki, Director of the Centre for Philosophy in Africa at Nelson Mandela University, who took up his post in October 2018.

“You can’t biologise or racialise culture. My idea of knowing myself in the world is African, but my skin colour is not the determinant. This reduction of people to one template of colour is vicious racism and something that was weaponised by history. But it is not culture. Culture is a complex of multi-layered realties of knowing oneself and how one lives one’s life.” These are the words of Dr Sam Nzioki, Director of the Centre for Philosophy in Africa at Nelson Mandela University, who took up his post in October 2018.

“Through the Centre we question what the discipline of philosophy in Africa means for a scholar in Africa, and as an everyday person in Africa. The work of the Centre responds to the #FMF movement across the country’s call for a decolonised curriculum, which Nelson Mandela University embraces as one of the expressions of being an African university. We need to profoundly respond to this while at the same time not removing ourselves from the big world issues as a country and continent that is part of the world.”

Dr Nzioki explains that decolonising the curriculum is not easy given that the current curriculum traditions have existed for many decades. The question of ‘what is philosophy in Africa?’ is also not confined to the discipline of philosophy; it exists in all disciplines and the Centre is positioned to have a presence in all the disciplines at the university to address how to ask the big philosophical questions in mathematics, physics, pharmacy, psychology, education, economics et al.

“It requires transdisciplinary Africa-purposed research for which we do not have extensive research depth at this time,” says Dr Nzioki. “One of the first objectives of the Centre is therefore to conduct and stimulate inter-disciplinary, intra-institutional and inter-institutional philosophical research with a focus on developing a canon, maxims and concepts for thinking that are purposed for Africa and Africanity.”

The work of decolonising the curriculum necessarily also addresses what to do with basic education as learners do not enter university with critical thinking skills.

“The Centre is therefore thinking about how to develop a bold packaging of philosophical processes to engage school learners, students, teachers, lecturers and postgraduates in the critical thinking tools of logic, knowledge creation and how to think and live ethically.”

Ethics, Dr Nzioki explains, is not just about life orientation, it is a rigorous of way of asking questions and taking responsibility for being in the world. This is the foundation of a living philosophy from which a philosophy in Africa can develop. It is also essential in this time, with leaders and public servants finding themselves on the wrong side of ethics.

One of the cornerstone questions is ‘what is it to do philosophy as a way of life?’ It borrows from the ancients where philosophy is not just a play with ideas, it is a vigorous combat of the mind and self; a constant realisation of ‘I don’t know but I continue to learn’. The Centre proposes this as one of its main ideas and it is looking for likeminded people with whom to engage, including students as intellectual activists across all disciplines where philosophy has the power to dispose them differently, in how they relate to the environment, other people and the self.

What is inspiring is there is a revitalisation of young people wanting to study philosophy and ask the questions of life. The students in Dr Nzioki’s philosophy classes are from the sciences, humanities and law, and they are taking it as a subject not a module.

In 2018, a group of mainly undergraduate students from a broad range of disciplines created the Thinkers Collective. “They asked me to give them a meeting space, and they meet on Fridays. I encourage them to think about philosophy as a way of changing how they think about life and problem-solving. It’s exciting to witness them increasingly questioning the binary view of reality; reality is not that simple.

“They are also debating the big decolonisation questions about how you emancipate yourself and give yourself capacity even if you come with tools from a bad legacy. They explore how to use these tools to sharpen their world; to unlock tenacious prejudices, including race and identity politics, and hegemonic capitalist issues.”