There is a scientist whose name is etched in coastal and marine conservation in South Africa. She is marine ecologist Dr Kerry Sink from the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) in Cape Town.

Sink has a reputation for innovative thinking and groundbreaking conservation in the marine and coastal environment. She pioneered the Green Trust supported Southern African Sustainable Seafood Initiative (SASSI) which got suppliers and consumers of fish and seafood across the chain hopping with conservation vigour.

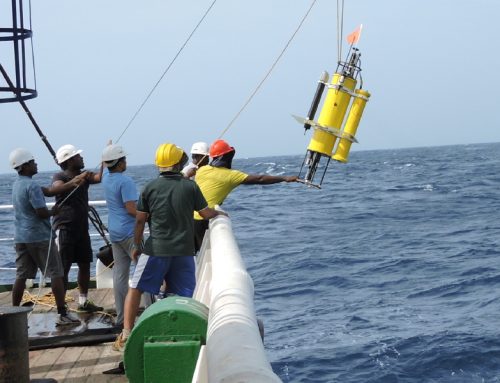

Now she is putting together South Africa’s first comprehensive National Marine and Coastal Biodiversity Assessment, with funding from The Green Trust and collaboration with a host of marine and coastal-related departments and institutes.

“In 2004 the first National Spatial Biodiversity Assessment was undertaken, reporting on the status of 36 broad marine biozones for South Africa,” says Sink. This time round a detailed assessment of coastal and marine habitats is being done. It will draw on over 500 scientific publications, research, expertise, projects and maps. It will report on the current status of marine and coastal biodiversity throughout South Africa and identify priority habitats, species and actions that need to be taken to protect them.

“South Africa has exceptional marine biodiversity with approximately 2000 fish species and at least 10 000 species of invertebrates and plants. Many species, an estimated 33%, are found only in South Africa and our knowledge of the vast majority is hopelessly inadequate,” says Sink.

“Drawing on projects like the Offshore Marine Protected Areas Project and the Reef Atlas Project we have mapped 136 coastal and marine habitats for the first time. We have assessed their ecosystem threat status – in other words which ecosystems are critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable – and their protection status – in other words, which ecosystems are protected within a Marine Protected Area (MPA) and which are not protected at all.”

Sink says that of the 136 coastal and marine habitats, 46% are threatened and 40% are not represented in MPAs. In other words, they have zero protection. Most of these habitats are offshore, in waters deeper than 30 metres.

The National Biodiversity Assessment reports on this and identifies priority actions. “For example, we need to identify areas that are sensitive to mining and we need to work on incorporating biodiversity concerns in mining applications, exploration and production,” says Sink. “Down the line we will need to list certain sensitive and threatened coastal and marine ecosystems in the Biodiversity Act to halt impacts on them.”

The priority actions being drawn up are done so in collaboration with many stakeholders, including fisheries, mariculture, mining, scientists and conservation organisations such as WWF.

The National Biodiversity Assessment also reports on the state of marine resources, based on research and recent reports on resources, such as the report published by the Department of Fisheries last year. “This will assist us in prioritising research and conservation action for the more than 500 caught species,” she explains.

The National Biodiversity Assessment also looks at key thematic elements such as climate change, alien and invasive species and the state of biodiversity knowledge.

With climate change we are looking at identifying priority actions to protect marine and coastal ecosystems that play a critical role in climate change adaptation,” Sink explains. “Beaches, dunes, estuaries, mangroves, kelp forests…these all need to be maintained in an ecologically functioning state in order to buffer the coastline from extreme events, such as large waves and coastal erosion linked to changes in wind strength and increased storminess.”

She explains how healthy, functioning estuaries need to be open to reduce the risk of flooding. When they silt up or they don’t flush quickly enough, it can cause backflooding, which can have a severe impact on human settlements. Estuaries are dynamic hubs of conservation importance because they link land, sea and freshwater, and serve as an important nursery area for many offshore species.

Coastal dune systems are also buffers against climate change as they alter in response to the wave energy, whereas if you build hard structures in this area, you disrupt this process and leave yourself vulnerable, Sink explains. “The Cape Flats, for example, are very vulnerable to climate change and are at risk of flooding. But if you have intact coastal dune systems along that foreshore and wise coastal development, you are going to have protection and buffering.” South Africa’s foreshore is already compromised in places with inappropriate developments and roads and it should not be further compromised.

“If you think that 17% of South Africa’s 3100-kilometre coastline has developments within 100m of the sea (both rich and poor) these areas are very vulnerable to the symptoms of climate change, such as a rise in sea level rise and increased storm frequency.”

Regarding the monitoring and control of alien and invasive species, Sink says: “The spread of alien and invasive species is complex with many potential marine pathways, including shipping, mariculture and the petroleum sector,” explains Sink. “For example, alien mussels from the North East Atlantic were introduced to our marine environment probably through shipping and further spread by the mariculture industry. Farming of alien species is risky as they can escape into the open sea.”

The seawater in the ballasts of ships also poses a threat because, for example, a ship might take in seawater in Europe and travel to Cape Town where it releases the water, along with alien species, such as the European shore crab. This crab has taken hold in some of our harbours but it hasn’t yet escaped into the wild.

An important part of the SeaChange project will be to encourage civil society to participate in the assessment and conservation of coastal and marine biodiversity. The Reef Atlas Project is a good example of how this can be done where scuba divers throughout South Africa over the past three years have helped us map South Africa’s reefs for the first time, Sink explains. No double she’ll think up several innovative projects over the next couple of months, which we’ll share with you.

“We are going to need the collaboration of all South African citizens, government departments, citizens and industries to make this work,” says Sink.