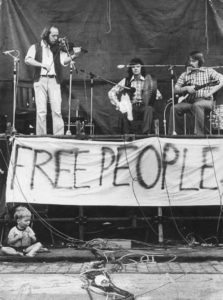

It has been 46 years since the first Free Peoples Concert was held at Wits in 1971. Back then, as always, music was a way for everyone to imagine and be part of a different South Africa – starting on campus.

It has been 46 years since the first Free Peoples Concert was held at Wits in 1971. Back then, as always, music was a way for everyone to imagine and be part of a different South Africa – starting on campus.

It was South Africa’s Monterey, Haight-Ashbury, Woodstock; a platform for counterculture with music as the vanguard. For a few special hours, it was another country where the great heart of music enveloped the crowd.

“It was a song that made it all possible,” says the founder of the Free People’s Concert, David Marks, a Durban-based musician, music producer and archivist of 3rd Ear Music. The song was Marks’ ‘Master Jack’, which hit the American charts in 1968, rising to number 18 on the Billboard Top 100.

“What struck me was how lucky I’d been with ‘Master Jack’ when there were so many musicians in South Africa who weren’t being recognised because of the times. So when I got my first royalties in 1971 I used them to begin promoting, recording and presenting South African singer/songwriters and township jazz musicians. Adding to this, a concert sound system was sent over to me at no charge by my friends at Hanley Sound in the United States. Parts of the sound system were from the iconic 1969 Woodstock Festival. My goal was to organise a free concert and offer our great musicians a platform.”

“In the same breath it was an act of defiance against Connie Mulder, the Minister of Information (incongruously a Wits PhD), who was clamping down on the few existing mixed hotspots for music. It was a case of ‘no blacks; no women; no dogs’,” says Marks.

And so it was that Marks launched the first Free People’s Concert on a beach in Durban 1970. The following year it moved to Wits. The lineup included Wits first-year student Johnny Clegg and his new music partner Sipho Mchunu, as well as the Mamelodi group Malombo and Ahmed Mukhtar. It was free to all and any donations from the audience went to the educational NGO, Teach Every African Child (TEACH).

“Wits University was one of the very few venues in the country where we could present mixed bands and audiences; it was a place where township and suburb could meet,” says Marks.

To organise the concert, the 3rd Ear team worked with student leaders from the SRC and NUSAS’s cultural wing, Aquarius. “Many of these student leaders went on to become latter-day luminaries in government and the media; some were chased into exile. One or two, like Craig Williamson, were state spies, but him we’d rather forget.”

Over the years the Free People’s Concert grew into a major national happening, attracting a crowd of 28 000 in 1985. The focus was unreserved freedom with an anti-apartheid undertone. South Africa was at war; the townships were in flames and many South Africans, including Wits students and academics, were in jail or underground or in exile. Anyone who opposed the status quo was sjambokked, shot at and dragged into police vans, even if they were doing nothing more dangerous than dancing.

The Free Peoples Concert offered respite. It opened its doors to people from every race and sector of South African society and explored the nation’s shattered psyche and unclaimed future through the music of the times. All the while, apartheid was tightening the chokechain on the nation, with an ageing PW Botha wagging his presidential finger and warning about the swart gevaar.

The concert used a loophole in the law: if the event was a private function, entrance was free and the musicians or entertainers played for free, there could be no restriction on who attended. This worked for a number of years until permits were required.

The venue also had to be changed to accommodate the swelling crowds and administrative opposition. From the swimming pool at Wits in 1971, it spilled over to the library lawns, then off campus to Milpark and finally to Kelvin. Every year there were stumbling blocks in its path. In 1976 the National Education Board issued a state edict that “non-whites” might not attend “this Woodstock-type open air festival on the campus” without the necessary permission. The Department added that “according to government policy, mixed gatherings of any kind are not encouraged as a rule” and that it contravened the Group Areas Act.

The Free Peoples gave the police and government “the jitters”, as an article in Wits Student put it. They got the jitters at the sight of black and white musicians and concert goers having a thoroughly good time together. They baulked at the sight of Sammy Brown flaunting his sultry moves at the Free People’s in ’75 when he called on the audience to do the same, as his backing band Cheyanne got right into the groove. At the same concert, musician Jeremy Taylor made a surprise visit home from Britain. He’s remembered for ‘Ag Pleez Deddy’ but what he should be remembered for is his 1960 anti-colonial anthem, ‘Piece of Ground’.

“Despite apartheid and all its laws, there were many very good people exploring and sharing thoughts of humanity, community and freedom through music, and the Free Peoples personified this,” continues Marks.

“Today, the term ‘struggle icon’ is applied to so many of our top musicians when they die, but it destroys them in history because they played such an important role simply by playing jazz or South African rock or being part of the vivid cultural life of Dorkay House in Eloff Street. Here, musicians and performers of every creed and colour would come together to create new sounds and new stage productions for a different country. It needs to be emphasised that they made a difference without having to hold what has become the requisite struggle card.”

In the beginning the Free Peoples Concert acts were mostly folk and soul singers, but this rapidly expanded to include the full spectrum of South African music in the 70s and 80s – from the raw South African rock of the late great Wits alumnus James Phillips, to the haunting Zulu chant of Wits alumnus Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu, to the marabi/kwela groove of Mango Groove with Wits alumna Claire Johnston’s arresting voice in the lead.

In every single act the Free Peoples lineup showed what a vibrant, fun, non-racial, free South Africa could be like. No one can forget the Cherry Faced Lurchers intoxicating the audience with their signature ‘Do the Lurch’, followed by their anti-apartheid theme song ‘Shot Down’, while the police circled in the streets or mingled in all-too-conspicuous civvies among the concertgoers, wearing, as Marks puts it: “slightly skew wigs, army issue boots under their jeans and slightly visible revolvers”.

Wits alumnus, writer and editor Shaun de Waal wrote that songs like Phillips’ ‘Shot Down’, ‘Brain Damage’ and ‘Darkies Going To Get You’ “evoked the terrible emergency years and spoke directly to the hearts and minds of a youth taking a cold hard look at who they are as white South Africans”.

At the concert, you could hear all the songs the SABC refused to play. These were the songs that inspired Lloyd Ross and Wits architecture alumnus and lecturer Ivan Kadey to start Shifty Records in the late 1970s. They recorded non-commercial South African music, the music of the Free Peoples Concert, including the mixed-race punk band National Wake, of which Kadey was a member.

De Waal described the mood of the 70s and 80s as “the new South Africa in twisted embryo”. He wrote: “We detested the apartheid state, and we reviled the Calvinist morality that came with it.” In revolt, a subculture of young, mostly white, politicised South Africans threw consequence to the wind as they lost themselves in the music.

Some of the many great musicians spanning those 16 years included: the Genuines, Benny B’Funk and the Sons of Gaddafi Barmitzvah Band, Kalahari Surfers, éVoid, the Aeroplanes, Tighthead Fourie and the Loose Forwards, Richard Jon Smith, PJ Powers and Hotline, Dr C, Splash, Afrojazz Pioneers, Steve Newman and Tony Cox, Afrozania, Nyanga, Mike Dickman, Via Afrika, Horn Culture, Radio Rats, Wasamata, Larry Amos, Psychoreptiles, Midnight Hour, Spectres, Believers, Bright Blue, Unhinged, Winston’s Jive Mixup, the Kêrels, the Abstractions …

In its way, the Free People’s played an underestimated role in breaking down all sorts of barriers, racial, ideological, cultural, subcultural and gender. “One of many vivid examples in my mind is of a group of Hell’s Angels dancing around a bonfire with members of the SRC after one of the concerts,” says Marks.

The Hell’s Angels had roared in to see what these Wits “communists” were up to. “They landed up partying with the ‘communists’ and helping to clear up and burn the refuse from the day’s events to make sure there was no mess afterwards.”

For Marks, the Free Peoples Concert was a story about living and surviving the times. And it should not be forgotten. “It took a lot of people giving freely of their time to put on those concerts,” says Marks, who subsequently organised other major concerts like Splashy Fen. He adds that he generally withdraws from events that grow beyond what they were meant to do. For him, the Free Peoples was an exception: “It did remain true and it is important to safeguard the memory of these gems in the strange, strange world we live in.”

New Book Project Documents Free People’s

The Hidden Years Music Archive Project (HYMAP) has launched a two-year Oral History and Book Project to document the history of the Free People’s Concerts. The project aims to connect with musicians, organisers and audience members who were present and involved with these festivals from 1970 to 1986. It is supported by the Volkswagen Foundation and the Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation at Stellenbosch University. If you were there and would like to share your memories, photographs and recordings from the Free People’s Concerts, please contact Dr Lizabé Lambrechts at lambrechts@sun.ac.za.

Johnny Clegg (BA 1976, BA Hons 1977, DMus honoris causa 2007)

“Sipho and I performed at the Free People’s Concert circa 1971. Our Zulu dancing team also performed there. At one level it was an exuberant and innocent event, as artists spoke and performed from stage. At another level it was a unique event in that many of the singer/songwriters who performed there were challenging the status quo and were given a unifying platform at a time when the national cultural environment emphasised separation and exclusion.”

“Sipho and I performed at the Free People’s Concert circa 1971. Our Zulu dancing team also performed there. At one level it was an exuberant and innocent event, as artists spoke and performed from stage. At another level it was a unique event in that many of the singer/songwriters who performed there were challenging the status quo and were given a unifying platform at a time when the national cultural environment emphasised separation and exclusion.”

Claire Johnston (BA 1990)

“I was in matric and 17 years old when I attended my first Free People’s Concert in 1985 with a group of school friends from Greenside High in Joburg. I was having singing lessons with the legendary Eve Boswell but I was not yet on stage. I was simply a member of the audience there to see my obsession at the time, the bands éVoid, EllaMental and Petit Cheval.

“I was in matric and 17 years old when I attended my first Free People’s Concert in 1985 with a group of school friends from Greenside High in Joburg. I was having singing lessons with the legendary Eve Boswell but I was not yet on stage. I was simply a member of the audience there to see my obsession at the time, the bands éVoid, EllaMental and Petit Cheval.

“We managed to get in front of the stage when this strange band called Mango Groove came shuffling on. They all stood in a line and there was no lead singer but I was impressed by their marabi/kwela fusion and original sound. One month later I was in the band practising at Dorkay House in Eloff Street. As it happened, one of the guys in the band had asked Eve Boswell to recommend a female singer and she suggested me. Our first gig was at the Hot Tin Roof in Rosebank and from then on it was me on stage performing with Mango Groove at the Free People’s, at the same time as I was doing my BA at Wits in Philosophy, Politics and English.

“I realised how small my life had been. Wits and Mango Groove opened my eyes hugely. We could not perform at some venues because we were a multiracial band, or the police would arrive and there would be violent outbreaks. It was ‘welcome to the real South Africa’.

“Thirty years later I think we are definitely in need of another Free Peoples Concert, to draw on the power of music to break down barriers and bring people together. It would be a brilliant thing to do and there is so much inspiring South African music to showcase. There is real heart in this country, South Africans are resilient and resourceful and our country is worth fighting for.”

Like a chunk of one’s youth flashing by

Cape Town-based author Glenn Moss was Wits Chair of NUSAS in 1971, the first year of the Free Peoples Concert at Wits. That same year he became Vice-President of the SRC.

“Thinking back to that first concert is like a chunk one’s youth flashing by. I was in second year and David Marks pretty much organised the whole thing, assisted from NUSAS’ side by our cultural committee Aquarius, led by Elaine Unterhalter. She went into exile in the mid-70s and is now a Professor of Education and International Development at the Institute of Education, University of London.

“NUSAS recognised culture and music as incredibly important in exposing students to multiracial environments and building a community of resistance. In developing levels of political resistance you have to develop a whole life engagement around it as an alternative community to students’ existing community. A free, multiracial concert was certainly part of this; an act of resistance in the early 1970s.

“Johnny Clegg was in the first lineup and it was also his first year at Wits; he majored in social anthropology. Like many of the musicians of the time, he was musical and political. From 1971 he started working with the Wages Commission as he was fluent in isiZulu and he translated the Wages Commission’s newspaper and pamphlets.

“Professor Guerino Bozzoli was the Vice-Chancellor at the time. He was well known for his resistance to apartheid educational policies and the government’s attempts to clamp down on student activism and protest.

“These were highly charged times. In October 1971 Ahmed Timol, who was working underground for the Communist Party, died, four days after being detained by security police. Officers claimed he committed suicide by jumping from the 10th floor of John Vorster Square Police Station, now known as Johannesburg Central Police Station. All these years later, an inquest is under way to reveal the real reason for Timol’s death. Wits medical student Salim Essop was arrested with Timol and he testified at the recent High Court inquest hearing.

“Alongside the anti-apartheid activism on campus in the early 1970s, there was an international counterculture movement, in the spirit of the Paris protests and the anti-Vietnam protests in America. Marches and protests became far more spontaneous on campus. Prior to this, marches were in academic gowns. The mass-based participatory political environment provided the perfect context for the Free People’s Concert.

“I think it was the first time that such an extensive outdoor event took place on campus. There were thousands of people, many from off campus, and a large number of black people. People were casually dressed; a lot of jeans and T-shirts and colourful, flowing, hippie-style clothes. As political students in NUSAS we identified with the ethos of the counterculture and freedom but not with the drug culture of hippiedom. It was far too easy for the security police to use drugs as a reason for arrest.

“For many Wits students, the Free Peoples Concert offered a sense of something special and something unusual happening, with talented musicians and a multiracial audience enjoying themselves in the sun. It offered a sense of what a different society could be or what a different ‘normal’ could be.

“It’s so important to remember that there was this vibrant happening in our history during these oppressive and difficult times. Wits can be extremely proud of its vibrant culture of resistance; it was the epicentre of new things happening that spread out elsewhere and this contribution needs to be celebrated.”

Free Peoples Concert 12 March 1972

Joburg-based musician and Wits alumnus Paul Clingman (BA 1973) was one of the Free People’s musicians.

Joburg-based musician and Wits alumnus Paul Clingman (BA 1973) was one of the Free People’s musicians.

“In thinking back on the Free Peoples Concert of 1972, there are conflicting emotions, as with everything to do with the past. Of course I was very young – only 21 – and the ideals and the music were everything I lived for. I was writing songs and what my songs stood for – the breaking down of barriers, the possibility of seeing, hearing and sharing the cultural and human experience of others – was encapsulated in some way by that day.

“The cultural censorship I experienced at that time at the hands of the only media outlet available then – the SABC – and the commercial censorship I experienced at the hands of the timid recording industry was for me overcome on that day. It was the first time I was able, along with everyone else there, to make myself part of another world – one devoid of the laws that interfered with life, and one connected in spirit with the world beyond our borders, in which freedom to be and say and think and create were paramount, valued – and possible.

“There was an atmosphere of almost unreal resonance and opportunity in that little moment – of a place in which the artificial barriers were more than surmounted – they were eliminated. No artists were paid. No tickets were bought, but we knew that donations made to TEACH were a tangible expression of what we stood for.

“I was doing a postgraduate HDip Ed at Wits at the time, so the venue was very familiar to me – indeed it was one of the only places where such a show could even have been contemplated, let alone successfully mounted. The response was amazing. The audience came too – thousands. There were families, children, and they came from all sorts of backgrounds and places. To see them all mixing freely in front of me, identifying with what I was doing, and celebrating the defiance and determination of simply being there, was exhilarating.

“For once I was able to stand on a stage not only saying and singing the things I was saying and singing, but actually, by my presence there, able to be those things as well. In later, harder years, when I was touring in townships, and so many more of my songs were proscribed and prohibited, and even today – still writing – I could look back at that little moment in which a certain hope was realised.

“Other concerts like it would follow in time, but in many ways, being before its time, the Free Peoples Concert was something that stood outside the days that hemmed me in, both physically and artistically, and remained a moment that not only promised a possibility, but embodied that possibility.”

The 1982/83 Free Peoples Concert

Gavin Rabinowitz (BA 1983, LLB 1985) was the SRC’s Chair of Culture and one of the organisers of the Free People’s Concert in 1982/83. He left South Africa for London in 1987 to avoid being drafted into the South African Defence Force. He did a Master’s degree at the London School of Economics, qualified as a lawyer and worked as a partner in an English law firm for a number of years before setting up his current business: a financial service company investing in real estate and other assets.

“I had run the Wits Jazz Club for a year and was very involved in music. When I was appointed to the SRC one of my roles was to help organise the Free People’s Concert, which was the climax of Orientation Week.

“David Cohen was Chair of the orientation committee and I was Vice-Chair. We had a huge amount to organise, including the venue, permits, acts, food, drink, security, stage, sound and so on. At the time I was 22 years old and in my final year of my BA studying Law and Psychology. I was very excited to be arranging what was then one of the largest open-air festivals in South Africa. I was completely undaunted by the task – I guess that’s the beauty of youth and naivety.

“The challenge was not to find suitable acts for the concert, because everyone wanted to play at it, but to find a suitable venue which could accommodate so many people and the non-racial mix. Eventually we found a wonderful site in Roodepoort, slightly further out than we wanted but in a beautiful natural setting.

“The list of performers included Johnny Clegg and Juluka, Steve Newman, Paul Clingman, Splash, Via Africa, PJ Powers, éVoid and many more .The aim was, of course, to have a wonderful music festival but also to expose the musicians to such a large crowd.

“On the day of the concert David and I arrived early in the morning to meet the security crew. They arrived with dogs – poodles! David and I laughed so much, wondering how this would intimidate anyone.

“The headline act was Johnny Clegg and Juluka. I stood on the side of the stage to watch it. The sun was setting on what had been a beautiful sunny day, the crowd was absolutely mesmerised by the band. I will never forget the look on all their faces, sheer joy and exuberance. I get goose bumps just thinking about that moment.

“A week after the concert the security police called me, I thought it was David Cohen joking with me. Eventually I realised it was not him. Two cops came to see me at my parents’ home and produced a recording of Splash (one of the bands), singing about freeing Mandela, a song which they said was banned. They asked me for a statement and for the band’s details. I said I was too busy on the day and that I did not remember what they sang about and had none of their details.

“I feel very fortunate to have been given such a wonderful opportunity to do something that was so well appreciated and attended. Not many have the chance to work with wonderful people and arrange something so substantial at such a young age. Moreover, we were never daunted by it; instead, we all pulled together and despite the really dark times, we had a huge amount of fun.

“It is definitely time to reawaken the Free Peoples at Wits. Music is a great bridge; it’s a cliché but true.”

I came along to feel free

“I came along to feel free,” said Wendall Pietersen, described as “a Coloured man” in an article in the Rand Daily Mail on Thursday 1 June 1972. On the same page, a large headline read: ‘Nationwide campus unrest escalates’. The article reflected on Wits Student’s coverage of the Republic Day celebrations, with a front cover picture of sheep being herded down a narrow street and a caption which read: “A nation celebrates”. The article challenged South Africa “to look at itself, at all the deaths in detention, malnutrition, poverty, break-up of families, detention without trial and asked the following question: How willing are we to make the most elementary personal sacrifice for the sake of humanity we shout so loudly about?

WITSReview tracked down Pietersen all these years later and he shared some of his memories and how his life has turned out:

“I was 23 in 1972 and completing my Honours degree in Social Work at the University of the Western Cape where I also lectured in the department. This was the only university open to ‘Coloureds’ at the time (save for very few seats at Wits but I think these were only for Medicine). At the concert I was also helping to organise collections of clothing and blankets for the less privileged as part of an initiative called ‘Operation Snowball’.

“Many years have since passed but that was not an easy period in the country and my experience at university was very hectic. I left the country in 1978 as my involvement in community action projects was seen by the government as political incitement. I moved to America where I completed my Master’s Degree in Social Work at the Graduate School of Social Work, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“I then moved to Italy in 1980 where I have lived ever since, acquiring Italian citizenship in 1986. I am married to an Italian citizen and we have two grown-up daughters, 33 and 30 years old.

“I have my own company, Pietersen Consulting, and I do consulting, facilitation and executive coaching in leadership development with various organisations around the world.”