A South African-developed coding programme called Tangible that teaches problem-solving through simple, fun games, and works with or without computers, has been accepted by the international UNICEF-led Learning Cabinet. This places it alongside a small group of international education tools that have been independently assessed for safety and scalability for real learning impact.

Tangible was developed by the Department of Computing Sciences in the Faculty of Science at Nelson Mandela University and is being implemented globally by the not-for-profit Leva Foundation. https://tangible.levafoundation.org/

Prof Jean Greyling doing Tangible coding with a visually impaired learner.

In the most popular Tangible game called Rangers, which is suitable for all learners from eight years upwards, the aim is to guide your ranger though an obstacle course to catch the rhino poachers. Each level presents a new challenge. At the same it teaches learners about the need for rhino conservation.

Another game called Juicy Gems, for Foundation Phase learners (five to nine years), has a farming theme. Two other games for eight years upwards are Speed Stars – a Formula 1 racing game – and Code Cup – a soccer game.

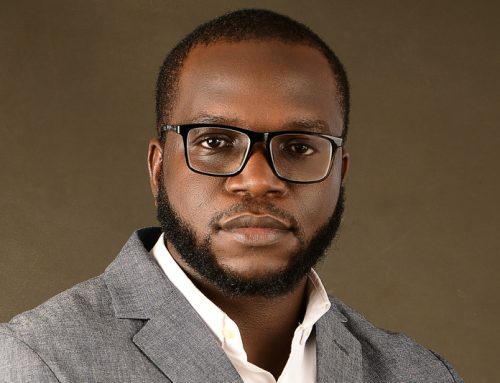

“Tangible’s selection by the Learning Cabinet followed a rigorous evaluation process that included academic impact studies,” says Professor Jean Greyling, Head of the Department of Computing Sciences at Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha who has coordinated the Tangible coding project since inception.

““We need to equip all learners for a future shaped by technology and artificial intelligence and the Learning Cabinet inclusion is an important acknowledgement of an approach that was designed for classrooms everywhere, irrespective of their resources or lack of them,” adds Greyling.

South Korean learners engaged in Tangible coding.

The Learning Cabinet https://www.learningcabinet.org/ is a joint EdTech initiative between UNICEF, the Asian Development Bank, Arm Holdings, and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. It showcases high-quality, evidence-based education tools that have been independently assessed for their safety, scalability and real learning impact.

“This will open many doors and opportunities for us to share our approach with education decision-makers in different countries and supports the programme’s continued expansion,” says Greyling. Tangible is already active in several countries and cultures, including South Africa and nine other African countries, Ireland, South Korea, Cyprus, Germany and Indonesia. To date, it has reached more than 350,000 learners worldwide

“Our goal is to reach learners worldwide, across very different classroom contexts,” he says. “In South Africa, over 16,000 schools lack computers, which is why Tangible is designed to work with or without technology, without being limited by either.

Greyling adds, “Tangible starts by making learning fun and accessible for both teachers and learners, while teaching the fundamentals of computational thinking and problem-solving. Through the process, many learners gain the confidence to pursue mathematics, which is essential for STEM careers.”

In every country, Tangible offers well-structured lessons that comply with the coding and robotics curriculum from Grade R to Grade 7 in South Africa, and the equivalent levels in other countries. The Tangible team in the Department of Computing Sciences has developed a number of coding games with different levels of complexity to suit all ages. Specialised formats have also been created for autistic and visually impaired learners.

Tangible coding at Salt River High, Cape Town

The programme is fully unplugged in the Foundation Phase (Grades R to 3) and introduces optional digital tools at later stages, using any smartphone.

More than 200 CAPS curriculum-aligned lessons for Grades R to 7 have been compiled and distributed at no cost to teachers across South Africa via Tangible’s WhatsApp Chatbot. During the 2025 pilot year, approximately 3000 teachers registered for this service, which empowers them to teach the gazetted Coding and Robotics curricula in their classrooms.

Tangible has grown steadily since 2017, when BSc Honours Computing Sciences student Byron Batteson developed the foundational coding app at Nelson Mandela University and subsequently teamed up with the Leva Foundation.

According to Leva Foundation chief executive Ryan le Roux, the organisation’s role is to ensure that the programme grows without compromising quality or consistency. “Tangible opens the door to learning. Leva provides the systems, partnerships and governance that allow it to scale responsibly,” he says.

One of the programme’s most visible public moments each year is the #Coding4Mandela tournament, held during Mandela Month. In a recent tournament, 50,000 learners from across South Africa and other African countries took part. One of the first participants, Buhle Pikoli from New Brighton in Gqeberha, who had never been exposed to coding or computers, completed all 35 levels in two days. “Today my life changed,” he said at the time. He has since completed his studies and is now a software developer.

In 2025, Tangible hosted a global coding World Cup with 340 teams from 30 countries participating online across five continents. In many of these countries, Amazon Think Big Spaces have been the anchor partnership that has launched Tangible into a global movement. South African schools placed first and second, with strong competition from Indonesia, the previous year’s winner. “The World Cup really showed how we are closing the digital divide,” noted Le Roux.

Another highlight in 2025 saw 400 learners play Tangible’s coding game in the children’s zone at the Las Vegas Grand Prix. One of the participating groups was led by Casey Juliano, a well-known IT educator in the United States, a STEM Hall of Fame inductee, and the teacher of the 2025 Robotics World Champion school team.

“For students to be able to engage with coding and pre-coding experiences that develop critical thinking, problem-solving and grit — it’s been the highlight, besides meeting the drivers and pit crews, of course,” commented Juliano. “I’m excited to explore how I can integrate this into my classroom, so my students have a strong scaffold before moving on to Python later.”

“That experience reinforced a key principle behind Tangible’s design: tools that work in under-resourced classrooms are as relevant in well-resourced ones,” says Jackson Tshabalala, Leva’s Engagement Manager. “The learners all play the same coding and robotics games. No specialist equipment required. No ideal conditions. Just learners working things out together through play.”

As education systems worldwide grapple with how to prepare learners for a technology-driven future, Tangible’s inclusion in the Learning Cabinet highlights a South African contribution to a global challenge: making foundational digital skills accessible, practical and scalable without leaving anyone out.