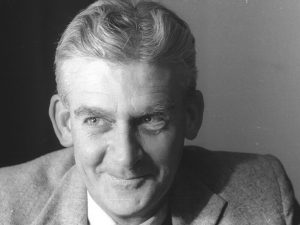

He was a gigantic, unsung character with unsurpassed knowledge and understanding of South African plant species, veld types and veld management. Landbou Weekblad salutes South African botanist and man of the veld, the late great John Acocks.

He was a gigantic, unsung character with unsurpassed knowledge and understanding of South African plant species, veld types and veld management. Landbou Weekblad salutes South African botanist and man of the veld, the late great John Acocks.

By Heather Dugmore

In the Footsteps of Acocks is the working title of a book about the contributions of John Acocks, currently being written by Professor Timm Hoffman, the Director of the Plant Conservation Unit in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Cape Town.

“I am approaching the end of my own career and I am back with Acocks,” says Hoffman. “I am driven by his vision of what caused our veld and landscapes to be in the state they are today, and where they are headed in the future. Some of what he saw and wrote about in the 1950s, 60s and 70s remains cutting edge and relevant, and reflects what our climate scientists are saying today.”

Acocks, Hoffman explains, who was born on 7 April, 1911, in Cape Town and died on the 20 May, 1979, in Middelburg, Eastern Cape) had a profound love for South Africa’s natural environment and was extremely concerned about how it was changing over time. He didn’t just talk about it; he spent endless hours walking in the veld during his 44-year career from 1935 (when he graduated with a Master’s degree in Botany from the University of Cape Town) to his death in 1979.

His first job was in 1935 when he was hired by the Department of Agriculture to conduct botanical surveys across South Africa. Ten years later he was transferred to the Division of Botany and Plant Pathology in Estcourt in KwaZulu-Natal for three years. From 1948 until his retirement in 1976, he worked at Grootfontein College of Agriculture in Middelburg in the Eastern Cape where he needs to be celebrated as one of its greatest sons.

It was here that he produced the first comprehensive, invaluable vegetation map of South Africa, culminating in his life work: The Veld Types of South Africa, published in 1953. In this memoir he classified the country’s vegetation into 75 different types and collected over 28 000 plant specimens from over 3000 sites throughout South Africa, with full lists of species names. His second book, Key Grasses of South Africa, was published posthumously in 1990 by the Grassland Society of Southern Africa.

Throughout his career he wrote incisively about the signs of environmental degradation he saw everywhere in the veld. These signs indicated to him the full extent of the transformation of the vegetation of South Africa as a result of detrimental farming practices dating back to colonial times and which are still ongoing.

The loss of palatable, climax species, particularly perennial grasses, was Acocks’ main concern. Acocks considered the loss of grass cover a national tragedy. He was convinced that grass cover had been lost from most veld types and would have been dominant throughout the country were it not for the impact of poorly managed domestic livestock. He presented the eastern Karoo as a specific case in point.

“He felt that poorly managed livestock had hoovered up the grasses and left behind the shrubby desert encroachment elements he saw over much of the Karoo at the time,” Hoffman explains. “He feared this would expand into the Free State grasslands unless veld rehabilitation farming practices were applied.”

In the 1960s Acocks coined the famous phrase: “South Africa is understocked and overgrazed”. He felt that veld degradation, which was and still is serious all over the country, was due to too few animals overgrazing the vegetation, combined with the soil being over-rested. Contrary to conventional agricultural thinking, Acocks believed that the impact of large numbers of livestock was needed to maintain healthy veld and grasslands.

One of the first people to research this, and someone whom Acocks studied, was French researcher André Voisin (1903 –1964). A biochemist, farmer and author, he discovered that overgrazing was a function of how long a plant was exposed to grazing, combined with how long it was before being grazed again. In other words, overgrazing is a function of time and not of animal numbers. Whether there’s one cow or 1 000 doesn’t alter the fact of overgrazing, it just changes the number of plants overgrazed if the animals remain too long in the same place or return too soon.

“Acocks understood this and from the 1960s he advocated a pioneering method of non-selective grazing (NSG), simulating the migratory herds, with heavy impact for short periods,” Hoffman continues. “He said this would stabilise the soil and restore the vegetation to its former ‘pristine’ state, dominated by climax grasses and palatable shrubs.”

“NSG is simply nature’s method of grazing,” Acocks stated in 1966. He explained that 14 days was the maximum period that livestock should remain in any camp, but recommended much shorter periods, which were not as achievable in his time as they are now, with the aid of electric fencing. Many misread Acocks, claiming he said that camps should be grazed for 14 days.

To develop the theory and practice for his approach (which was subsequently taken up by other southern Africans like Allan Savory, Johann Zietsman and André Lund), Acocks teamed up with several farmers. He was convinced that NSG should replace the conventional, rotational grazing system where livestock remains in large camps for extended periods. He explained that during these extended periods, livestock selects the most desirable grasses and grazes them repeatedly as soon as regrowth occurs, weakening their rootstocks until they are destroyed at which point less palatable species take over and dominate.

“The arguments about NSG or rotational grazing have continued but what is unquestionable is that Veld Types of South Africa and the four maps Acocks produced for this book are so far ahead of his time, it is remarkable.

“His maps show South African vegetation in a ‘pristine’ state which he set at AD 1400 and then tracked the impact of agriculture from this time to 1953 and then further to a projected 2050, revealing a devastated environment. What is interesting is that his 2050 map closely resembles some of the more recent climate change projection maps, based on the increase in CO2 where southern Africa will be devastated by a 2 to 4 degree temperature rise.”

His extensive field notes and photographs are invaluable in recording how South Africa’s veld and landscapes have changed over time. It is thanks to the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) nand the value they place on field notes and photographs that we have an archive of Acocks’ research. All of his notebooks and black and white negatives have been secured for posterity by SANBI. Much has been digitised and used in the development of ongoing efforts to map and document changes in the vegetation of South Africa.

Over several years, Hoffman has also been rephotographing sites first photographed by Acocks and other early botanists to contribute to the veld monitoring record. Nearly 2,000 historical photographs have been repeated, with the aid of students, colleagues and South African’s from all over the country, and thousands more are required. The database of historical landscape photographs is accessible to everyone via an on-line platform called rePhotoSA (https://rephotosa.adu.org.za) and all photographic contributions are welcomed.

How Hoffman “met” Acocks

“In the mid 1980s I was doing my PhD on arid and semi-arid landscapes under the supervision of Professor Richard Cowling from the Department of Botany at what is now Nelson Mandela University,” Hoffman explains.

“This brought me to the Karoo and as soon as you venture into the Karoo it is inevitable that Acocks’ ideas and contributions will cross your path. His Veld Types of South Africa, was Richard’s ecological ‘bible’ at the time and his passion and enthusiasm for John’s work was passed on to me. Regrettably, Acocks had died just six years earlier, in 1979, but I was able to meet and interview his widow, Ellaline.”

“John Acocks liked to work alone and he resisted promotion to senior management positions, preferring instead to spend his productive years walking through the veld, particularly that of the Karoo. He had very high standards and so research assistants did not stay long under his tutelage. He was a real mountain goat and would walk extremely far into the veld and make long lists of plants. He could identify just about everything he saw except perhaps for some of the fynbos and mesembs (vygies), which could catch him out. But for the rest, he had this uncanny knowledge of flora and veld and I am deeply honoured to be writing about him. I hope that others will be as inspired as I have been over the full span of my career by this remarkable South African ecologist.”

For more information contact Prof Timm Hoffman on:

Tel: 021 650 5551

Cell: 072 298 8169 (c)

Email: timm.hoffman@uct.ac.za

Rephotographing website: http://rephotosa.adu.org.za – dedicated to the repeat photography of historical landscapes of southern Africa