From 3 to 7 December 2018, experts from all over the world are meeting in Geneva to develop a globally binding agreement on marine plastic pollution and to stop the deluge of plastics in all natural environments.

Globally, WWF is one of the key actors driving the plastic initiative to convince governments to endorse a global agreement to stop the flow of plastics into natural environments. As part of this drive, the entire WWF network is advocating for national governments to support the adoption of a negotiating mandate for a new legally binding agreement on marine plastic pollution during the United Nations Environment Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya, from 11 to 15 March 2019.

At a national level, the WWF Nedbank Green Trust, funded by Nedbank, launched a major three-year Marine Plastic Pollution Programme in July this year to address marine plastic pollution at a number of levels. The programme involves clients, industries, retailers and the government to work towards urgently implementing practical approaches and policies to address the marine and environmental plastic problem collectively throughout its life cycle – from production and consumption to waste management.

‘No organisation can achieve this on its own. Because the plastic challenge is so huge and multi-faceted, it has to be addressed at multiple levels and sectors,’ says Tatjana von Bormann, the lead of Programmes and Innovation at WWF-SA who is also leading the Marine Plastic Pollution Programme.

Von Bormann describes plastic as ‘an extraordinary material’, which has revolutionised many aspects of our lives over the past 80 years. The problem, as she explains, ‘is that it is cheap and therefore widely used and easy to throw away. It doesn’t break down for a couple of hundred years, creating a serious source of pollution in our oceans, watercourses, wetlands and environments.’

Von Bormann cites some alarming statistics based on widely accepted research. Since 1950, an estimated 8 300 million tons of plastic have been manufactured – half of it since 2005. Only 25% of this plastic is still in use. Most of it is waste, as only small volumes have been recycled or turned into energy. The majority, if not captured in landfills, has found its way to the natural environment.

It is everywhere and literally choking our environment and all the species that inhabit it. And it’s not just the macro, visible plastics (plastic bags, bottles, containers, shoes, diapers and moulds) that are a problem. There is also the deadly problem of micro plastics (anything smaller than 5 mm in diameter) with so many resulting issues that most of us don’t even think about.

Von Bormann says examples of micro plastic include the synthetic fibres that come off our clothes, such as fleeces, plastic abrasives in household products or in cosmetic exfoliants and glitter makeup. Another example is nurdles – small plastic pellets about the size of a lentil, used to make almost all our plastic products. In October 2017, South Africa experienced The Great Nurdle Disaster, when billions of nurdles landed up in the ocean because a container fell off a ship during extreme weather off the KwaZulu-Natal coast, which severely threatened marine life as the nurdles were mistaken for food. The spill spread far and wide, with billions of nurdles washing up on our shores and as far as Western Australia.

Tyres are another example of invisible pollution. We’ve long known about the challenge of managing tyres, but we now also understand that, while in use, tyres produce ‘tyre dust’ – an impossible-to-manage micro plastic shed every time tyres rotate on the road and it washes into water systems through stormwater drains.

Micro plastic is in the air we breathe, our drinking water, the food we eat (particularly seafood), our oceans, cities and landscapes. We don’t yet understand enough about the implications for human health, but indications are that it could be toxic in so many ways. For example, plastic pollution on a reef makes it 20 times more vulnerable to disease, as discussed in a recent paper based on research on coral reefs over time, published in Scientific American, titled Where plastic goes coral disease follows (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/where-plastic-goes-coral-disease-follows/).

According to Professor Peter Ryan of the University of Cape Town’s Percy Fitzpatrick Institute, scientists have known since the 1960s that plastics are damaging to marine animals that get entangled in plastic waste or ingest it.

So what now?

‘The overarching objective of the Marine Plastic Pollution Programme is to eliminate the flow of plastics into the environment (through reduction, reuse and recycling) in a phased approach,’ Von Bormann explains. This includes:

- ·Promoting a client action campaign, similar to the WWF’s consumer-championed Southern African Sustainable Seafood Initiative (http://wwfsassi.co.za/). This highly successful initiative demonstrates that consumers have the power to drive change by supporting responsible suppliers and sellers.

- Shifting market practices to reduce waste and move towards a circular plastics economy by rallying producers/brands, retailers and all businesses to respond to the environmental and social risks associated with plastic pollution, and to demonstrate how they are reducing plastic use, recycling, reusing, and addressing the problem.

- Supporting the development and implementation of effective national plastic waste management policies and regulations, including a first step of sorting municipal waste, and engaging informal waste collectors in the process. This is also supported by an effort through the WWF international network to push for a global agreement to measure and reduce plastic pollution that enters our common marine environment.

Industrial engineer Lorren de Kock, who has a master’s degree in chemical processes, will manage this programme for the WWF Nedbank Green Trust from January 2019. ‘An expert with these qualifications is needed on this project, as it is such a fast-moving complex target,’ says Von Bormann.

She believes that plastic pollution is an opportunity to start thinking differently about economic models and recognising that natural resources are finite. ‘There is an economic opportunity to start thinking differently about plastics in line with circular economic models where companies can design plastics that can be reused, shared, repurposed and recycled. Solutions are emerging from all corners and the trend is gathering momentum throughout society.’

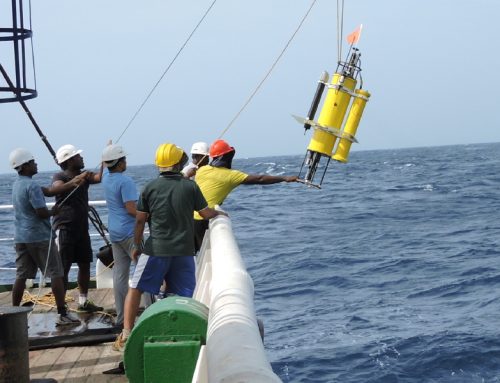

In the September issue of Forbes Magazine, for example, it published a story by geology PhD and science writer Trevor Nace titled The world’s largest ocean cleanup has officially begun. A $20 million floating multiple boom system was deployed from San Francisco Bay in September for testing. It was designed by an 18-year-old Dutch inventor, Boyan Slat, who is the founder of The Ocean Cleanup. Each boom will trap up to 150 000 pounds of plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch between California and Hawaii each year – a vortex of trash created from an ocean gyre in the central North Pacific. Slat claims the system will clean up half of the garbage in that area in the first five years.

‘As with climate change, time is not on our side, and solutions need to be fast-acting,’ says Von Bormann. ‘It is no doubt a crisis, but it is also one of the biggest opportunities ever presented to think differently, consume differently and take responsibility for our world. Changing our behaviour to address this environmental challenge effectively may just help us to develop the skill and understanding necessary to address some of the bigger, more intractable challenges. A shared interest in getting plastics out of nature could also be an important step in the big push necessary to shift towards a low-carbon society.’