Phosphate mining of the seabed, known as bulk marine sediment mining, has never been done anywhere in the world and is a major concern for leading marine scientists worldwide. Yet South Africa is about to become the testing ground. Despite significant objections, the Department of Mineral Resources has granted three rights to prospect for marine phosphates. Phosphates are predominantly used for agricultural fertiliser.

Phosphate mining of the seabed, known as bulk marine sediment mining, has never been done anywhere in the world and is a major concern for leading marine scientists worldwide. Yet South Africa is about to become the testing ground. Despite significant objections, the Department of Mineral Resources has granted three rights to prospect for marine phosphates. Phosphates are predominantly used for agricultural fertiliser.

This is an extremely destructive form of mining in which the top three metres of the seabed is dredged up, destroying critical, delicate and insufficiently understood sea life in its wake.

‘Two prospecting rights were granted in 2012 and one in 2014; these three rights extend over 150 000 km2 or 10% of South Africa’s exclusive economic zone,’ says Saul Roux, a legal campaigner for the Cape Town-based non-profit Centre for Environmental Rights (CER). An exclusive economic zone is the area of coastal water and seabed to which we have exclusive rights for drilling, fishing and other economic activities.

Roux is part of a WWF Nedbank Green Trust marine-based project called Safeguarding our Seabed. One of the objectives of the project is to pursue a moratorium on bulk marine sediment mining in South Africa, which he describes as ‘the height of irresponsibility’. Roux is a legal campaigner with a master’s in Biodiversity and Conservation and is currently completing his PhD.

‘There is already immense pressure on our oceans, with 98% of our exclusive economic zone leased for offshore oil and gas exploration or production, and only 0,4% officially protected. This is considerably below the commitment of 10% made in the Convention of Biological Diversity, which we signed,’ he explains.

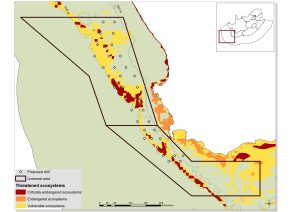

The marine phosphate prospecting rights have been granted in areas that overlap South Africa’s major fishing grounds, critically endangered seabed or benthic ecosystems and no less than nine proposed marine protected areas. The benthic zone is the ecological region at the seabed or sediment level, together with the subsurface layers. These are highly productive ecosystems that constitute the building blocks of larger marine systems as many species breed, spawn and feed here.

The prospecting rights extend from the northern reaches of the West Coast, down the West Coast to Cape Town, then around the peninsular and all the way to offshore Mossel Bay. The prospecting areas are located mostly in depth contours of between 200 m and 2 000 m, with the shallowest depth being 5 m.

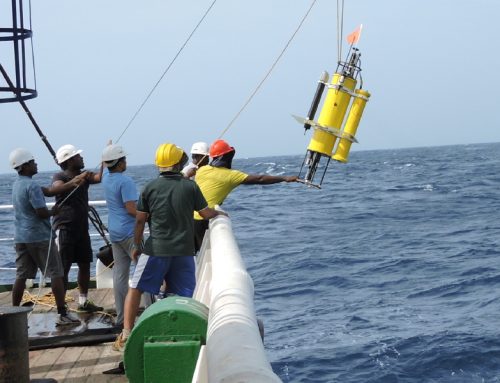

‘We are highly concerned about the type of technology used for bulk marine sediment mining, which is similar to strip mining the sea floor, with giant dredge vessels scooping up a three-metre layer from the seabed, causing the direct destruction of seabed habitats,’ Roux continues.

In addition to destroying the area, this kind of mining releases hazardous substances that are normally locked into the seabed, including radioactive materials, methane, heavy metals and hydrogen sulphide. This will destroy marine wildlife and cause many commercial fish stocks, including hake, to be unmarketable.

Roux elaborates that after the sediment layer is scooped up, it is suctioned on board the vessel where larger phosphate-bearing sediment is separated using significant quantities of fresh water in the process. The excess water and fine particulates are poured back into the ocean, creating a giant sediment plume that buries and smothers seabed ecosystems and disturbs the wider marine environment by impacting on water quality, photosynthesis and plankton.

The noise from the mining process will also directly affect and potentially damage marine mammals. The process is vastly destructive in a number of ways and research from around the world indicates that the impacts are potentially irreversible.

Three private companies have acquired the three prospecting rights of around

50 000 km2 each. South African companies Green Flash Trading 251 and Green Flash Trading 257 each acquired a right. The two Green Flash Trading companies are virtually identical. They were seemingly set up separately to create the impression that the owners would not have a monopoly, given the extent of the prospecting areas. The two Green Flash Trading companies have no experience in marine mining, and it would appear that they were established solely for marine phosphate prospecting. The other company, Diamond Fields International, is a Canadian mining company that holds marine exploration and mining rights in other jurisdictions.

‘These prospecting rights were granted by regional managers with no experience of dealing with offshore applications of this kind. Furthermore, our existing mining laws are wholly inadequate for dealing with seabed mining,’ Roux explains. ‘For one, our current Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act does not deal with offshore mining and there is no capacity for compliance monitoring and enforcement or to properly assess applications in terms of environmental and socioeconomic impact. These rights have been granted without sufficient knowledge of how marine ecosystems work and despite the fact that they overlap massive fishing grounds and critically endangered ecosystems. It is the height of irresponsibility.’

Roux adds that in 2013 when the CER applied for access to the information and policy documents regarding seabed mining that guided the Department of Mineral Resources decisions to grant these exploration rights, access was denied. An appeal against this denial of access met with no response.

Other countries facing marine phosphate mining applications have either denied them or placed a moratorium or permanent ban on bulk marine sediment mining. In Australia the government in the Northern Territory imposed a moratorium three years ago while further environmental and risk assessments are conducted. Namibia followed suit and placed a moratorium on marine phosphate mining in 2013.

In 2014 New Zealand denied applications for marine phosphate mining on the grounds that it irreversibly impacts on marine ecosystems and traditional and commercial fishing rights.

In 2016 Mexico’s federal environmental authority denied a licence for the Don Diego marine phosphate mining project on the grounds that the project would destroy the seabed-dwelling organisms, with a domino effect on many other species, including the endangered loggerhead turtles.

‘With the WWF Nedbank Green Trust funding, which came into effect in 2015, we are now working towards securing a moratorium on bulk marine sediment mining in South Africa through the Safeguard our Seabed Coalition, which we helped to establish,’ says Roux.

‘The coalition includes 11 member organisations who represent commercial and small-scale fishers, organised labour and environmental and environmental justice organisations, among others. The coalition has also been engaging with stakeholders in Namibia and other countries that confront similar seabed mining proposals. South Africa is a party to the Benguela Current Convention, signed with Namibia and Angola in 2013. The purpose of the convention is to align sustainable management of shared marine resources between our three countries for the human and ecosystem wellbeing for generations to come.

‘At the same time we are promoting effective marine spatial planning for South Africa and supporting the establishment of a network of new offshore marine protected areas, which were gazetted for public comment earlier this year but have not yet been proclaimed. Fortunately this is one of the marine conservation objectives of the government’s Operation Phakisa, which seeks to rapidly unlock our ocean economy.’

Roux says they need the South African public to be aware of the risk South Africa is taking with bulk marine sediment mining, which has been the subject of many independent studies, including studies by the World Bank, and all have advised against this form of mining, based on the precautionary principle.

‘We need to widen support for the moratorium and put pressure on the Minister of Mineral Resources and Environmental Affairs to recognise that the risk is far too great and to accept the precautionary principle and adopt a responsible approach to seabed mining.’

For more information go to www.cer.org.za/safeguard-our-seabed