“You are out there in the middle of hundreds of dolphins and it is amazing and overwhelming. The water is literally boiling with dolphins and gannets and you have to remind yourself that you are there for a reason – to gather data on these animals about which very little is known.”

Dr Stephanie Plön from the Department of Oceanography, School of Environmental Sciences at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, is one of the few people in the world who has several times experienced what it is like to be out at sea amongst a superpod of dolphins.

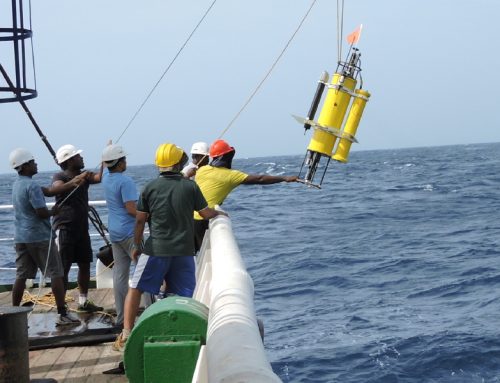

She specialises in dolphin and whale (cetacean) research and many regard her work as the ideal job but it is also seriously demanding, as she spends up to ten hours at sea in a six-metre semi-rigid inflatable, focusing on field notes and photography.

“You have to be fit because your body is on a moving platform for extended periods. You also have to be very aware of the ocean and weather conditions because it’s dangerous out there and you can get caught out by rapidly changing weather conditions and fog, when there is a risk of large ships driving into you,” explains Plön.

She counts herself fortunate not to have had any incidents, but her two years of training with the National Sea Rescue Institute (NSRI) in Port Elizabeth alerted her to how quickly the weather can turn or accidents can happen.

Originally from Göttingen, Germany, she completed her undergraduate degree in marine biology at Swansea University in the United Kingdom.

She moved to South Africa in 1994 as a result of her interest in dolphins and whales and completed her Master’s and PhD at Rhodes University, followed by Postdoctoral research in New Zealand.

“I have always been fascinated by dolphins, whales and the marine environment, because we know so little about this world and I am interested in finding out about the unknown,” explains Plön who settled in Port Elizabeth in 2005 to pursue research along the Eastern Cape coast and in Algoa Bay – home to the Long-Beaked Common Dolphin, Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphin and the Indian Ocean Humpback Dolphin.

“These species are not only important in their own right, they are key indicator species for overall ocean health because they are at the top of the marine food chain. Research on them informs the decisions and actions required to sustainably conserve our oceans and marine species,” says Plön, whose research team at NMMU includes four PhD students, three MSc students and one Postdoctoral Fellow.

Her team focuses on novel research on dolphins and whales, and Port Elizabeth is the ideal place to do this for a number of reasons, including the abundance of dolphins in these waters and the marine mammal collection at the Port Elizabeth Museum, which is the largest in the Southern Hemisphere and third largest in the world.

Established in the 1960s, the collection has been put together from dolphin and whale strandings, and animals incidentally caught in shark nets along South Africa’s coastline. It is a fascinating, invaluable repository for marine scientists worldwide. Algoa Bay is equally fascinating for scientists, with its unusually large group sizes of common and bottlenose dolphins. Part of Plön and her team’s research is to figure out why.

“We often have four or five sightings a day and because of the larger groups of bottlenose and common dolphins in Algoa Bay, we can see groups ranging from 10 to 15 bottlenose dolphins to several hundred common dolphins, often associated with bait balls or large schools of sardines or red eyes (part of the herring family). Sometimes these bait balls are a kilometre in diameter,” she explains.

“It’s crazy, it’s like a mini sardine run, with a feeding frenzy all around you, and, amongst all this you’re trying to observe and photograph the dolphins, because we need to identify individuals for our research, from notches or marks on their dorsal fins.”

While Algoa Bay’s bottlenose and common dolphin populations appear to have healthy population sizes, the Indian Ocean Humpback Dolphin is in serious trouble. It is now classified as ‘Endangered’ according to the 2015 Red Data Book of Mammals of South Africa (in press). The estimate is that the population has dropped to under 1000 individuals for South African waters.

The most recent research on the population size of the Indian Ocean Humpback Dolphin was in 1991 – 1994 when it was estimated that approximately 460 individuals resided in Algoa Bay. This indicated that historically it was the largest population in South African waters. Comparisons with current data suggest that their group sizes are down by half.

Updated population research on this dolphin is therefore of critical importance and in June 2015, postdoctoral researcher in NNMU’s Department of Oceanography, Dr Thibaut Bouveroux, started his research on the Indian Ocean Humpback Dolphins in Algoa Bay, under the guidance of Plön.

The population decrease could be related to a decrease in food availability and/or a range of human impacts – from shipping and fishing to pollution and paddle skis. Plön explains that the Indian Ocean Humpback Dolphin is an extremely shy animal that is easily disturbed:

“These animals live in the coastal zone within 500 metres from the shore where there is a lot of human activity, and this might have a negative impact on their reproductive rate or food abundance. Even paddle skiers surprise them when they get within a few metres of them, which is why I always advise paddle skiers to be on the look out for them and keep their distance,” explains Plön.

Plön and her team also recently started researching where and how far dolphins travel from Algoa Bay during the annual sardine run. They are comparing this to where and how far they travel outside of the sardine run, which starts off East London in late May/early June and moves up the coast to Durban.

“There is some scientific debate as to whether the sardine run actually starts in Algoa Bay, but it has not been confirmed,” says Plön. “What we certainly do have are bait balls and all this research helps to inform us about the dolphins’ diet, which includes reef and estuarine fish species, and whether these populations are stable or decreasing.”

Over the past seven years Plön and her team have also been researching the pathology of stranded Indian Ocean dolphins and comparing them to the dolphins incidentally caught in the KwaZulu-Natal shark nets.

“We know that strandings are in most instances a result of the animal being sick, whereas the by-catch animals should be reflective of the normal, wild population. The pathology investigation therefore significantly assists us in assessing the general health of South Africa’s oceans,” Plön explains.

Since 2009 parasite lesions have been detected in all the dolphin species, and both in the stranded animals as well as those caught in the shark nets. The specific parasite is yet to be identified, but marine parasites are increasingly being linked with ocean pollution.

One of her Master’s students, Inge Adams, is currently looking at 40 years of dolphin samples from the Port Elizabeth Museum to determine which parasites occurred previously and whether the parasite community has changed over time. A number of local and international collaborators, including geneticists, pathologists and parasitologists, are partnering in this research.

To share information about dolphins and whales, Plön and her team host exhibitions at Port Elizabeth’s oceanarium, Bayworld. They also give talks to ocean-focused sectors, such as the Surfski Club and Coega Environmental Management Committee, and they lead workshops for Eastern Cape Parks and Tourism rangers to promote citizen awareness about dolphins and whales, and dolphin and whale watching.

“South Africa’s marine environment is a global biodiversity hotspot,” she says. “Far more needs to be done to raise awareness about this incredible natural heritage, and the need to experience it and conserve it.”