Jan Oelofse was a legend. Few people deserve this accolade and he is one of them. Independent, brave and headstrong, he pioneered the mass game capture technique known as the ‘Oelofse Method’ that revolutionised game capture and the game industry in Africa.

Jan Oelofse was a legend. Few people deserve this accolade and he is one of them. Independent, brave and headstrong, he pioneered the mass game capture technique known as the ‘Oelofse Method’ that revolutionised game capture and the game industry in Africa.

“In game capture terms he was a genius. His contribution deserves the highest possible praise because he is the one who developed the unique mass capture method that enabled us to go from a handful of captured game species to several hundred in a month. He will go down in history as being one of the greatest animal capturers ever.” This is how Dr Ian Player, South Africa’s most celebrated wildlife conservationist, describes Jan Oelofse who worked for him from 1964 in what was then the Natal Parks Board.

Late last year Jan passed away from heart failure at the age of 79 on his and his wife Annette’s wildlife ranch in Namibia, but his name and legacy lives on, beautifully recorded in a recently published book titled ‘Capture to be Free’, written by Annette. It’s an incredible story of Africa, of wild adventures in Tanganyika, of Hollywood movies with John Wayne, of life and times in the Natal Parks Board, and of the Oelofse Method, which Jan originated in 1968 and which to this day is still the only method used for mass game capture.

It is fitting that Ian should be the one to describe Jan because together they paved the way for the growth of private game ranches in South Africa from 1970. Ian pioneered the capture and translocation of rhino and Jan pioneered the capture and translocation of large numbers of game.

Today, there are approximately 10 000 private game farms spanning 15-million hectares (and a further 15-million hectares for mixed wildlife and cattle farming) with over 18-million head of game, excluding the provincial and national game parks. Without the Oelofse Method this could not have happened.

The development of the Oelofse Method dates back to 1964 when Jan joined the Natal Parks Board as a game ranger, and they were having to cull 20 000 animals a year in the iMfolozi and Hluhluwe reserves, which could not support increasing numbers of game.

Rudimentary capture methods for game translocation were being used as an alternative to culling, but they were clumsy and ineffective. “We would chase the herds on horseback and try to catch them with nooses and nets, but too many animals got injured,” explained Jan in an interview after winning the Audi Terra Nova Award for the Oelofse Method a few years back. The cullings and the injuries got to him – he couldn’t stand seeing so many animals destroyed – and he threw himself into refining game capture. After plenty of trial and error, in 1968 he came up with his method of herding animals with the aid of a helicopter into a funnel-shaped capture boma, enclosed with plastic sheeting.

“They couldn’t see through the plastic so they didn’t try to charge through it,” he explained. Suddenly they could capture 450 wildebeest in two hours, herd them onto trucks and translocate them with minimal trauma.

In his Quarterly Report, Hluhluwe Game Reserve, 1968 he describes this breakthrough: “On the 4th September I was in a position to carry out an experiment which I had been planning in regard to eliminating the animals from running into the nets. The plastic ‘wall’ was so effective that even when the animals were chased they could not be forced to run into it.” At the same time he formulated another idea of building a wooden pen onto the capture boma, which led directly to the transport lorry via a ramp. “The game was successfully transferred to large wooden boxes positioned on the lorry without having to be handled. Ten animals at a time could be loaded. “It was a red letter day in my game capture career; something I had always hoped to achieve.”

Jan had not only revolutionised game capture, he had revolutionised wildlife conservation, aided by the handful of men who worked closely with him on the ground, including John Clark, Begifa Mhlongo, Drummond Densham and Charles Tinley, as well as the courageous capture backup team of mainly Zulu men on foot and horseback. From that time, vast numbers of animals could be moved to restock existing game parks and to open up new wildlife areas.

“I was very fortunate to join Jan’s capture team in 1969 at a very exciting and experimental stage of capture,” says Drummond Densham who first read about Jan in a feature in Farmer’s Weekly in the mid-1960s. “He was an incredible man who would think things through very thoroughly. When he would come to us and say ‘I’ve thought about this’, you knew he had, down to the finest detail. He was one of those characters who inspire exceptional team spirit. The Zulu capture team loved him and called him ‘inTshebe’ – the one with the beard. They saw how, irrespective of colour, he expected everyone to get stuck in and get the job done together.”

The perfection of Jan’s method was its simplicity, but the trial, error, perseverance and convincing his detractors that it could work required guts, dogged determination and the sustained support of Ian and fellow Natal Parks Board wildlife manager Nick Steele (one of Africa’s renowned conservationists). They cleared the way for him, often having to shield him from bureaucratic processes and barriers, which Jan characteristically bucked. While others were shaking their heads at Jan, Ian and Nick believed in him.

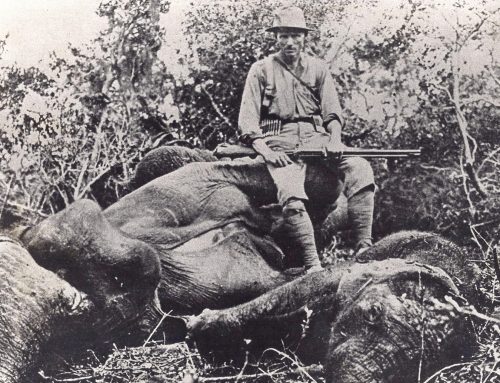

In his book ‘Bush Life of a Game Warden’ (published in 1979) Nick Steele described Jan as follows: “A typical Afrikaans-speaking South African, tall, with noticeably broad shoulders, he wears a small beard and despite thinning hair is a ruggedly handsome man of the veld, highly individualistic, an outstanding horseman and wild animal handler. His versatility made one understand why the English needed three years and half a million troops to conquer his forebears in the Anglo-Boer War”.

Jan worked for the Natal Parks Board until 1972 when he decided to go it alone, starting the first private capture business in South Africa. From here, with R700 in his pocket he moved to the Mount Etjo region of Namibia. He had grown up in Namibia on a cattle farm close to Etosha National Park, where game moved freely through their land, and to which he had always longed to return.

On his return he met Annette (nee Diekmann) who shared his love of wildlife and who had grown up on a 60 000ha cattle farm in the Otjiwarongo district. Headstrong and highly capable, from the age of seven she was already helping to run the farm and inoculating cattle.

“Jan’s plan was to buy land where he could set up a base for his capture business, but he didn’t have the money so he leased 5000ha of land, built capture bomas and pens and established his game capture operation which he called ‘Oelofse Wild’,” Annette explains. Moving game between South Africa and Namibia, after a few years he was able to buy the piece of land.

“There was never enough money to buy land but we did, with difficulty and facing some really tough times when we were almost down and out financially, but we managed to pick ourselves up and move forward and buy more land. During our 28 years of marriage we managed to expand our land to 30 000ha,” continues Annette.

She and Jan met and married when she was 23 and Jan was 51. “We had both been married before and you never want to hurt anyone but we were meant to be together, we were definitely soul mates. We spent every single day of our lives together, we were never apart and we never once felt the age difference. It was a perfect marriage, it was amazing.”

Together they worked tirelessly to achieve their same dream of developing their wildlife sanctuary.

To ease their finances and supplement their income from the capture business, they pioneered the trophy hunting business in Namibia. “Most of the buyers for the capture business wanted breeding herds, so we were left with a lot of male animals, which we released onto the land for trophy hunting and launched Jan Oelofse Hunting Safaris,” says Annette.

“The hunting and killing of wild animals went totally against our grain but we had to be pragmatic to make ends meet, and we did this by keeping the trophy hunting to a minimum, only taking out the old males, and adding a wildlife safari component, with a comfortable lodge,” explains Annette. They have four of the Big 5, excluding buffalo, plus over 30 different species of antelope, and their hunting and safari clients are predominantly from the United States.

Their son and only child Alex is now on the ranch with Annette and they are continuing with the dream. “He’s now 27 and he studied Mechanical Engineering at the University of Stellenbosch as we always wanted him to have choice, but after he graduated he came home and told us that this is the life he wants.”

Before he died Jan told Annette how happy he was to have achieved what they have achieved. “It was a rare moment of contentment as he was always striving towards something he wanted to achieve.”

Jan is buried on the koppie in the centre of their sanctuary. “You can see all the game from here and we often came here together,” says Annette. “It is where his soul wants to be.”

“They captured wild animals for zoos in Europe. Zoos were the in thing; people didn’t know better, and after reading an article about Willie, Jan, having just completed a diploma in agriculture, decided he wanted to work for him and drove from Namibia to Tanganyika (now Tanzania) to seek him out,” Annette explains.

It took Jan several months to get there because he ran out of money en route. He did ploughing for a farmer in Zambia and he worked as a construction supervisor until he had sufficient finance to continue his journey.

Finally arriving in Tanganyika he headed for Arusha and asked for directions to Willie’s farm. “I am Jan Oelofse and I am here to work for you,” he said to Willie who was not expecting him. The two clicked immediately and together they captured many species of animals, using the most rudimentary equipment, including nets, cages and a lasso or ‘vangstok’.

During this time a Hollywood classic called ‘Hatari!’ with John Wayne was filmed at Willie’s farm and in Hollywood. Not only was it was based on their lives they were also hired to work on the production. Jan was put in charge of ‘animal habituation’ or taming wild animals for the film. The wild cast included baby elephants, leopards and lions.

For the Hollywood part of the film shoot, Jan had to accompany 40 wild animals on a DC6 to the United States. While in Hollywood he was offered a job as a stuntman for Westerns but he turned down the job as he missed Africa too much.

He returned to Tanganyika but after independence his work permit was not renewed, which brought him to South Africa in 1964. Money was scarce and he did everything from posing as a life model for BA Fine Arts students to capturing flamingoes for the Pretoria zoo before applying for a ranger position with the Natal Parks Board. The then head of the Parks Board John Geddes-Page offered him a job.

For more information or to purchase ‘Capture to be Free’ contact Annette Oelofse on:

Tel: 00264 67 290 175/6

Email: jan.oelofse@iafrica.com.na

Website: www.janoelofsesafaris.com